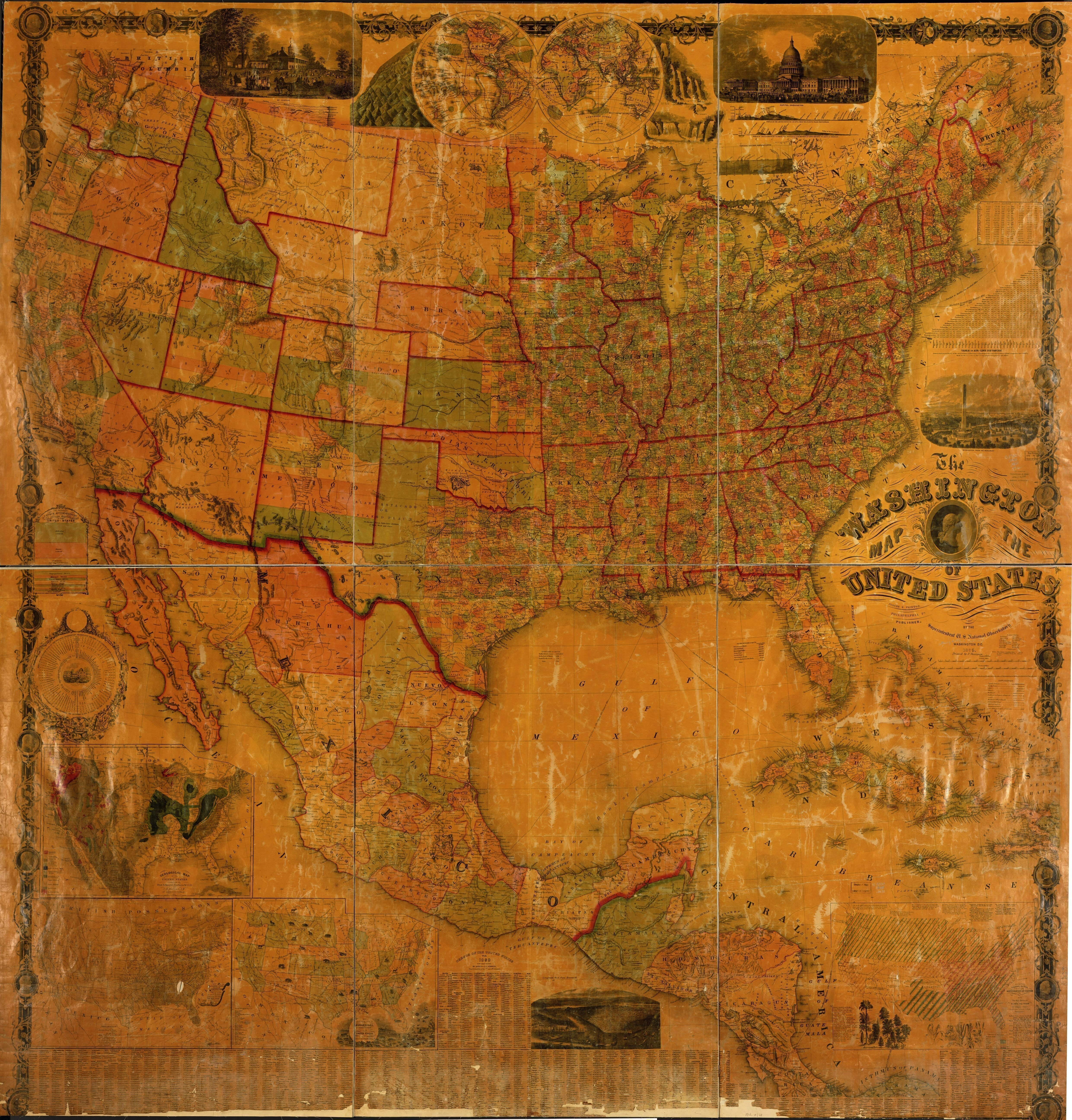

The 14th Amendment wrote the Declaration of Independence’s promise of freedom and equality into the Constitution. In early 1866, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction submitted a number of proposals to the rest of Congress, each addressing a specific problem. The proposals were then bundled into a single amendment. Finally, Congress added the Citizenship Clause. It was passed by Congress on June 13, 1866, and ratified on July 9, 1868.

Special thanks to Kurt Lash from the University of Richmond School of Law for sharing his research and expertise. Kurt Lash, The Reconstruction Amendments: Essential Documents (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Turn device horizontally for easier scrolling.

Event — February 16, 1833

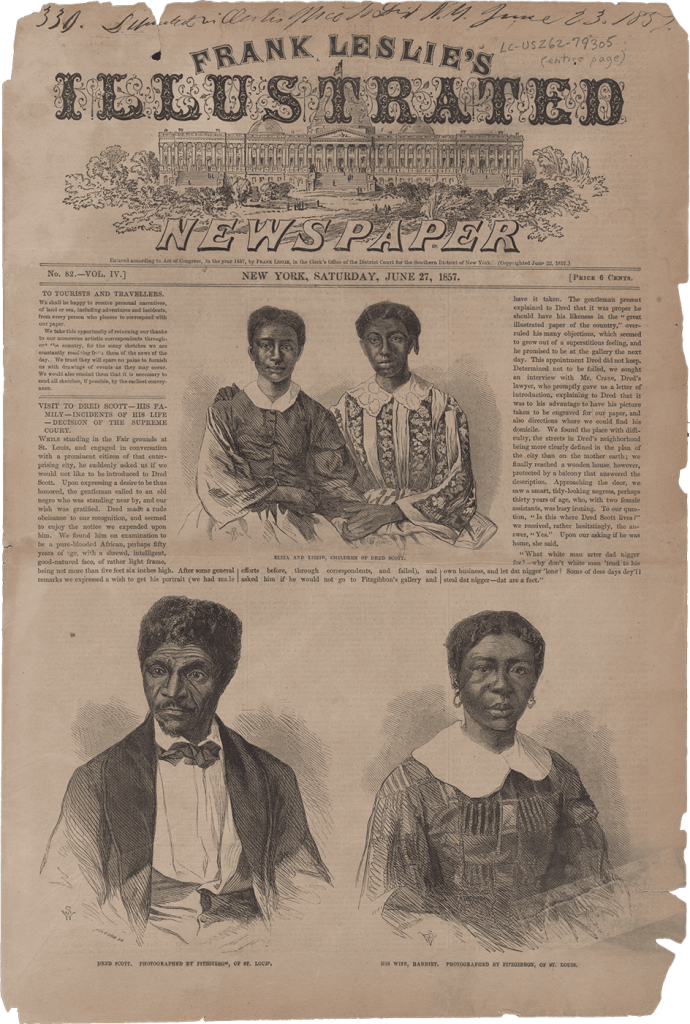

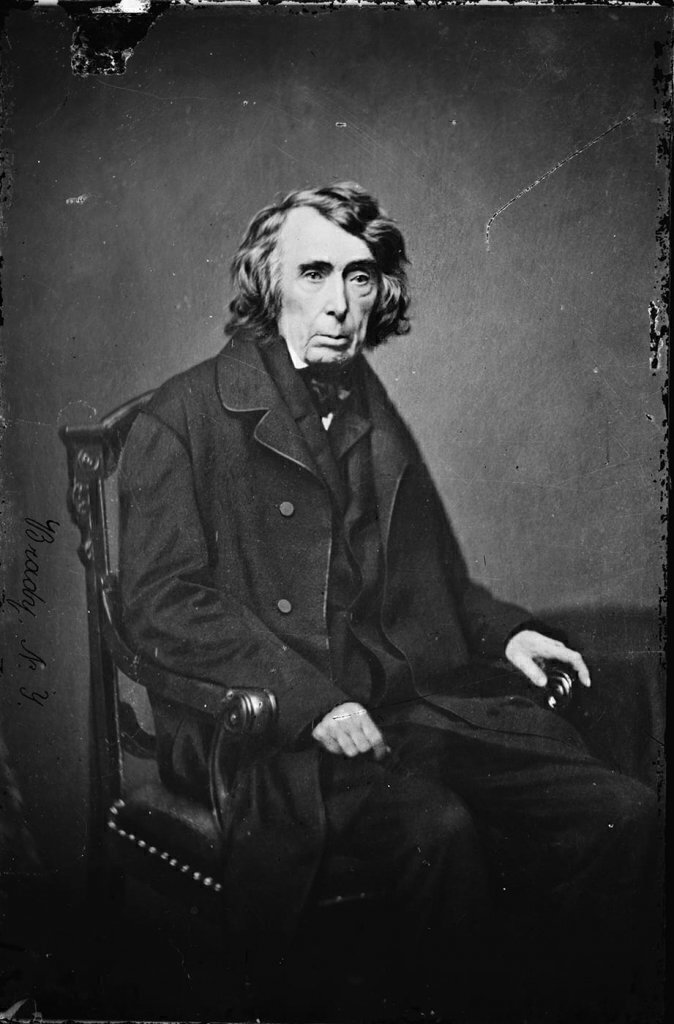

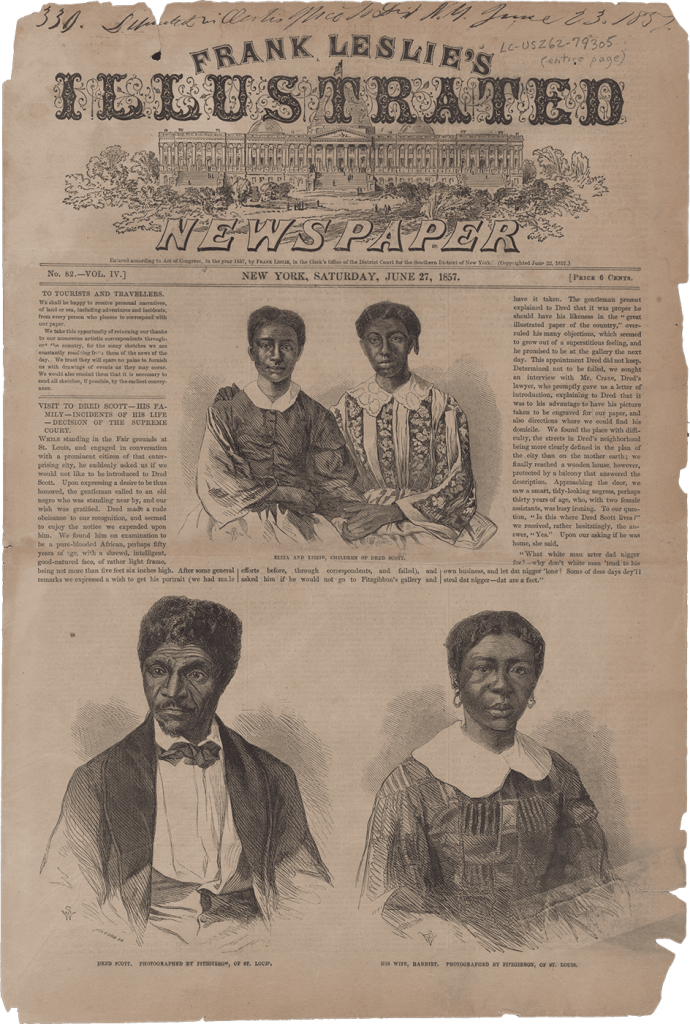

Event — March 6, 1857

Event — April 15, 1865

Event — December 4, 1865

Event — December 6, 1865

Event — December 13, 1865

Draft — January 12, 1866

Draft — January 12, 1866

Draft — January 22, 1866

Draft — January 27, 1866

Draft — February 3, 1866

Event — February 28, 1866

Event — April 9, 1866

Draft — April 21, 1866

Event — April 28, 1866

Draft — April 28, 1866

Event — April 30, 1866

Event — May 10, 1866

Draft — May 10, 1866

Event — May 23, 1866

Draft — May 29, 1866

Event — June 8, 1866

Event — June 13, 1866

Draft — June 13, 1866

Event — November 5, 1866

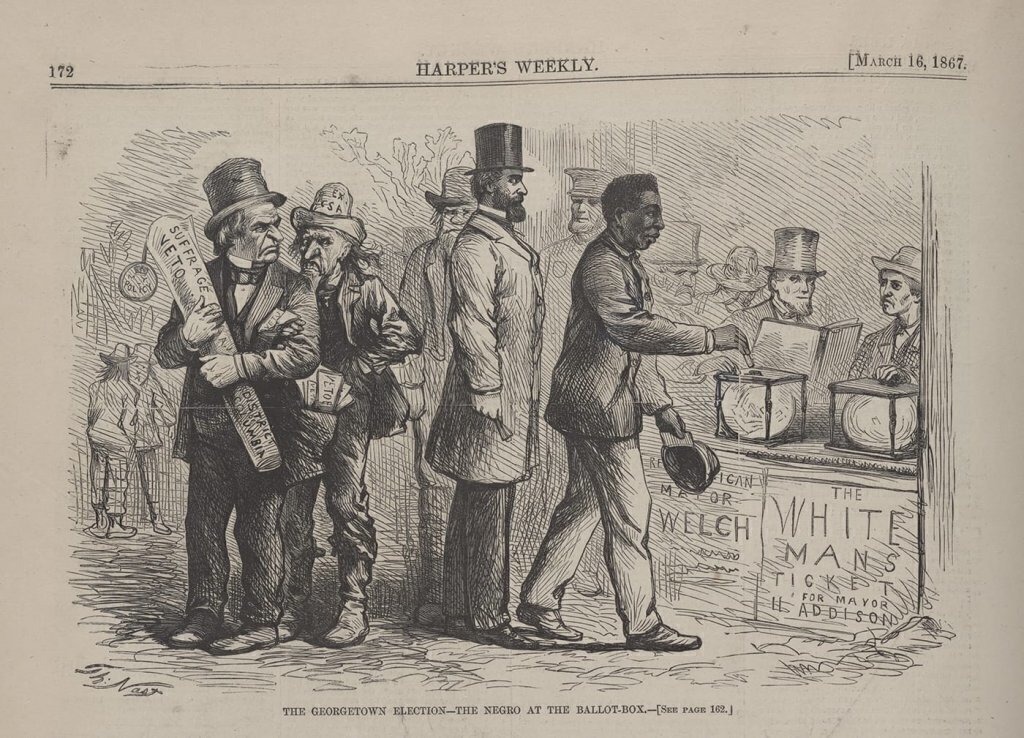

Event — March 2, 1867

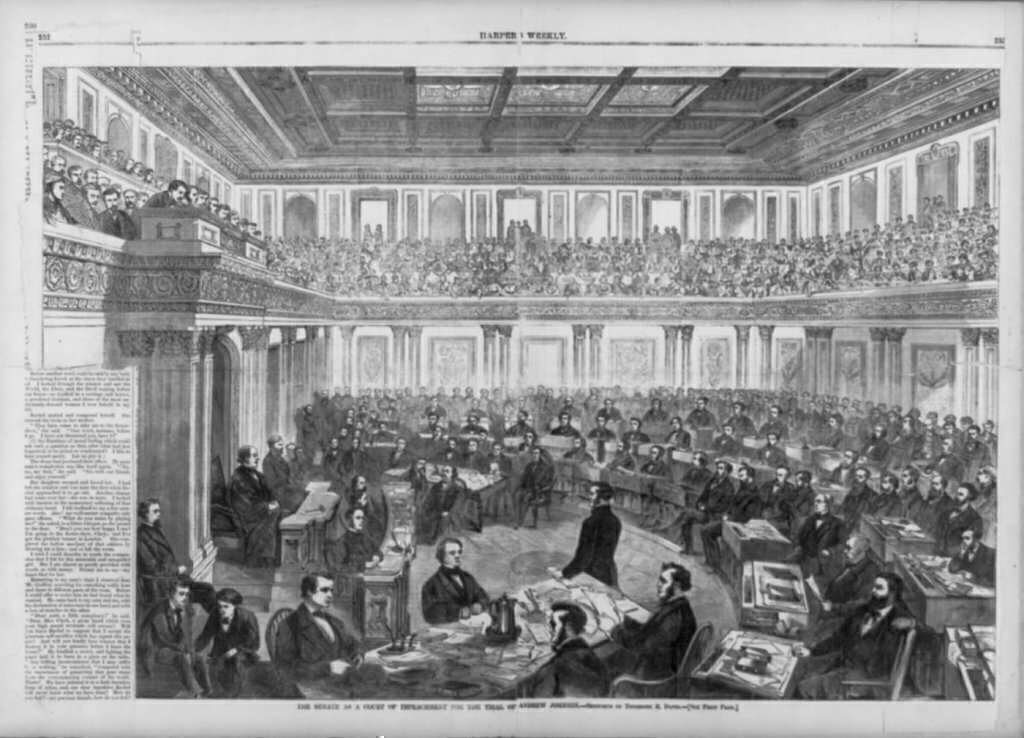

Event — February 24, 1868

Event — July 9, 1868

February 16, 1833

In the early 1800s, judges issued rulings that would later influence debates over the 14th Amendment. The two most notable were a federal circuit court decision in Corfield v. Coryell (1823) and the Supreme Court's ruling in Barron v. Baltimore (1833).

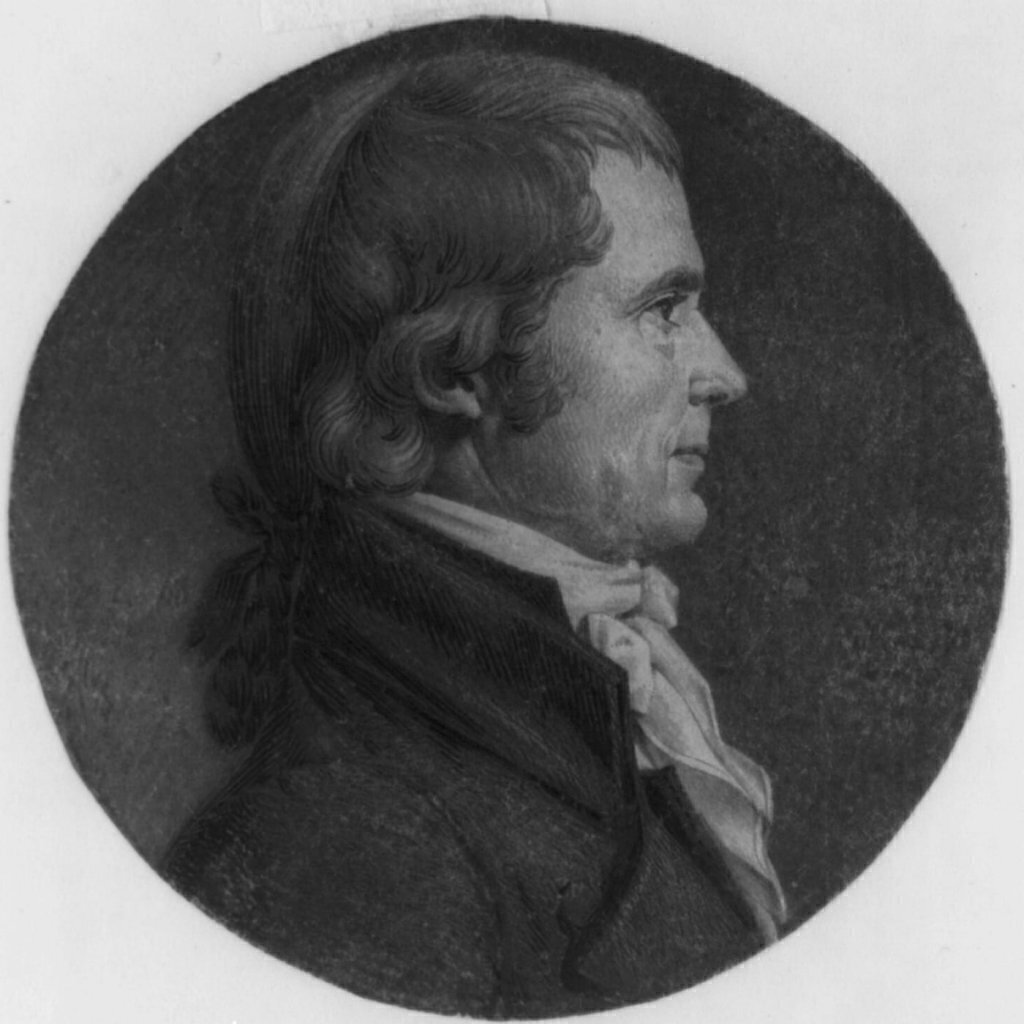

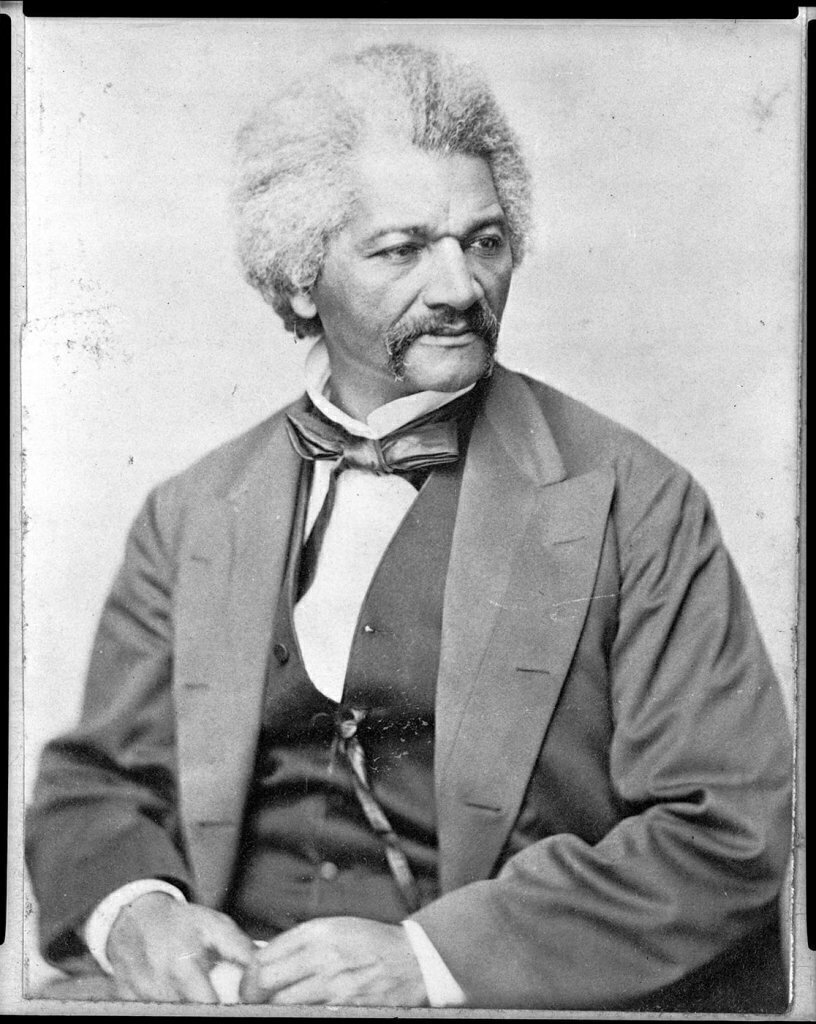

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court ruled that African Americans could not be U.S. citizens. Abolitionists condemned the ruling, and the new Republican Party sought to overturn the decision. In 1866, Congress included a citizenship clause in the proposed 14th Amendment in an effort to undo Dred Scott.

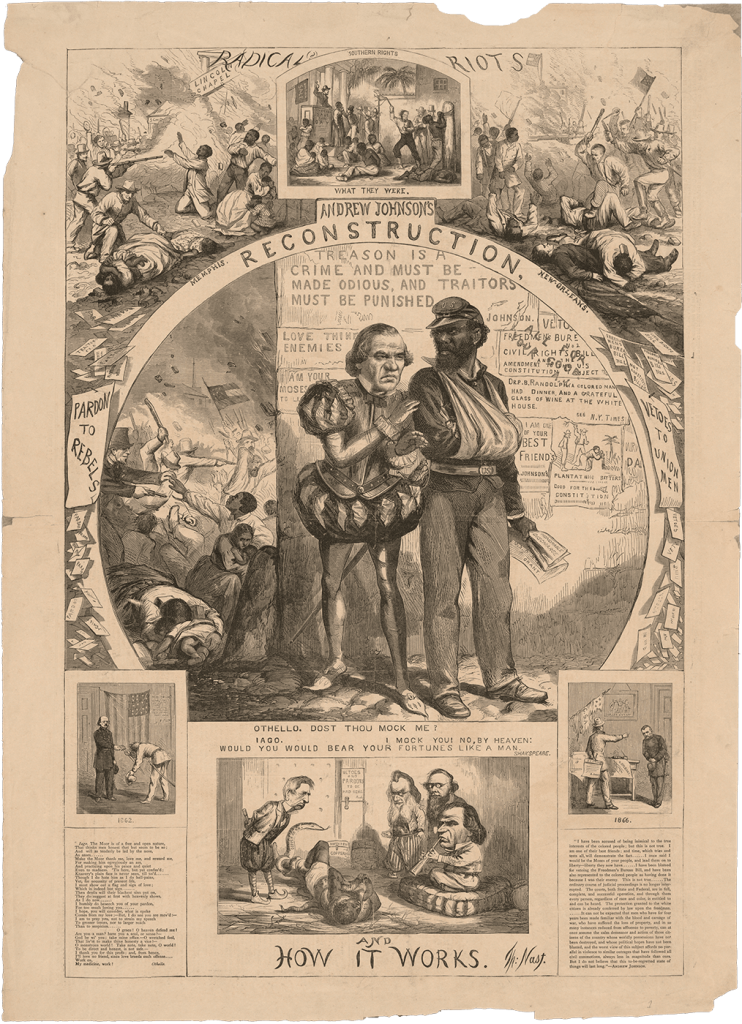

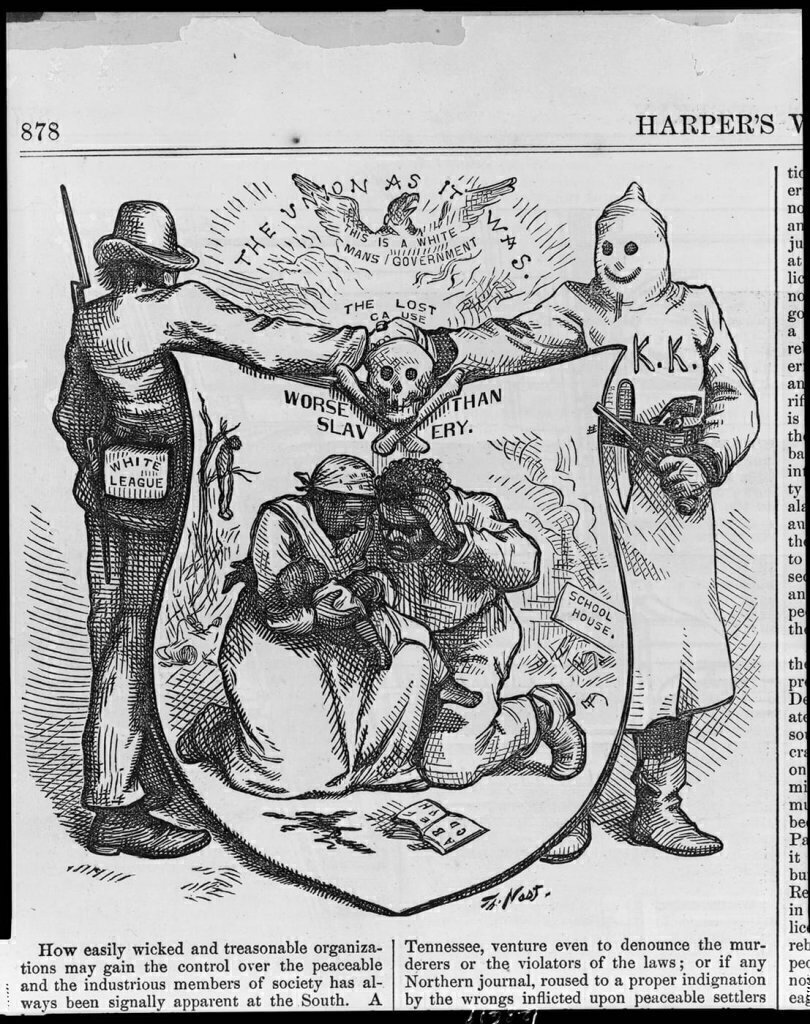

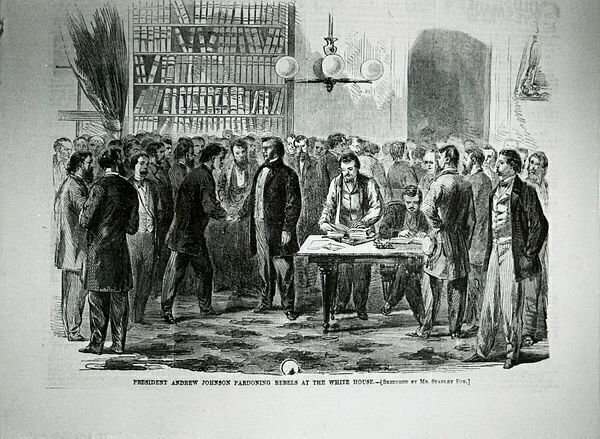

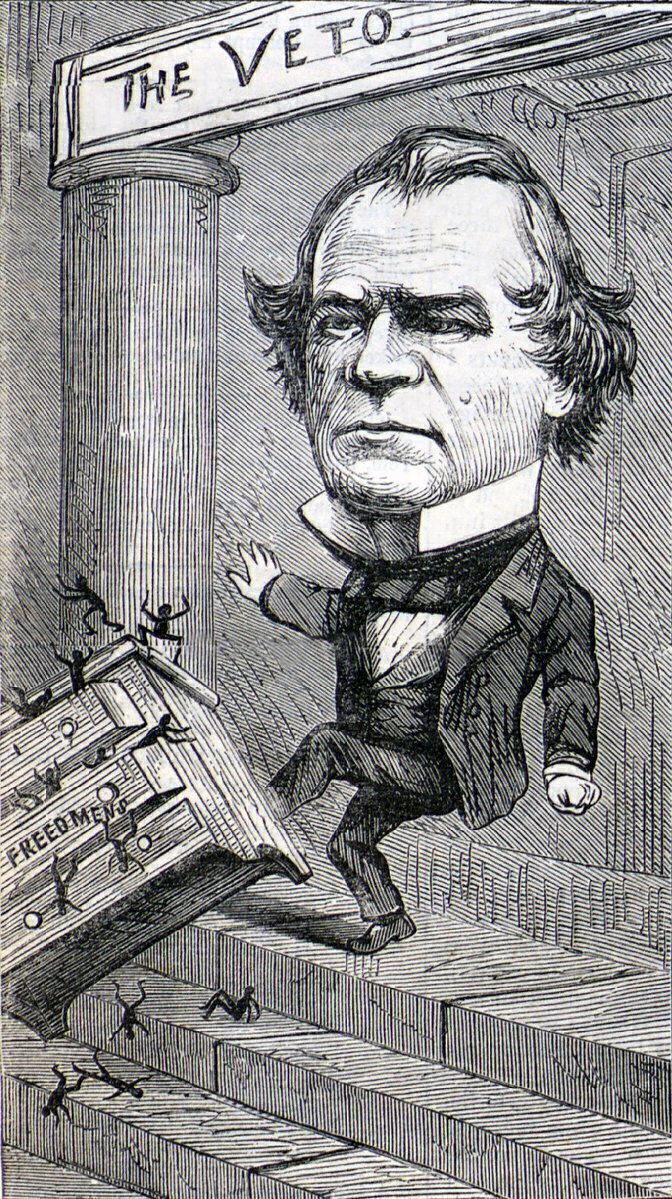

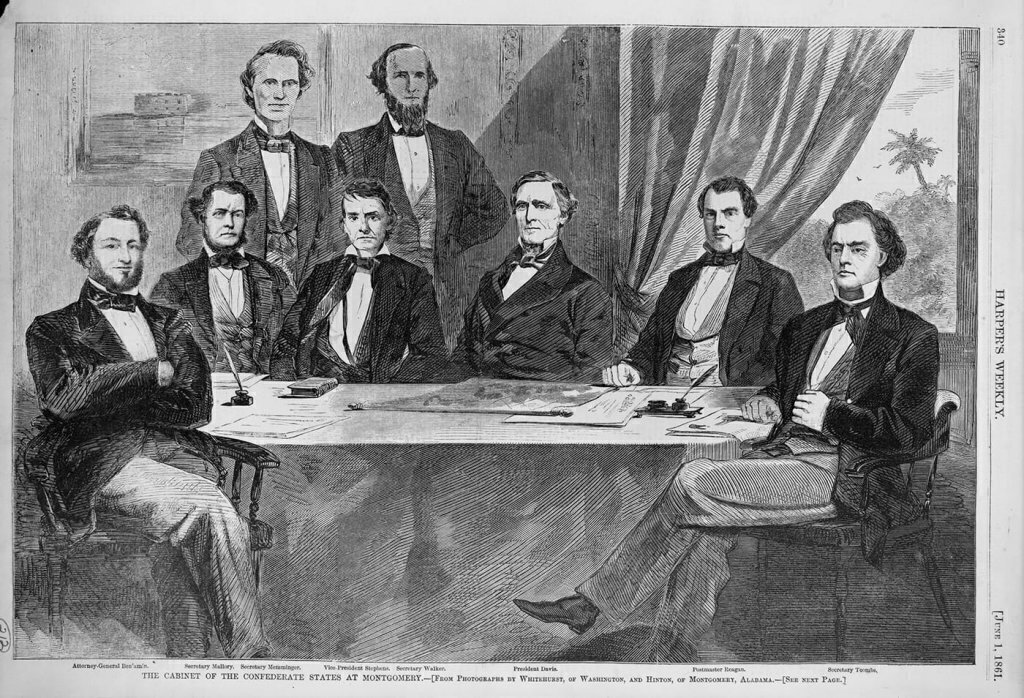

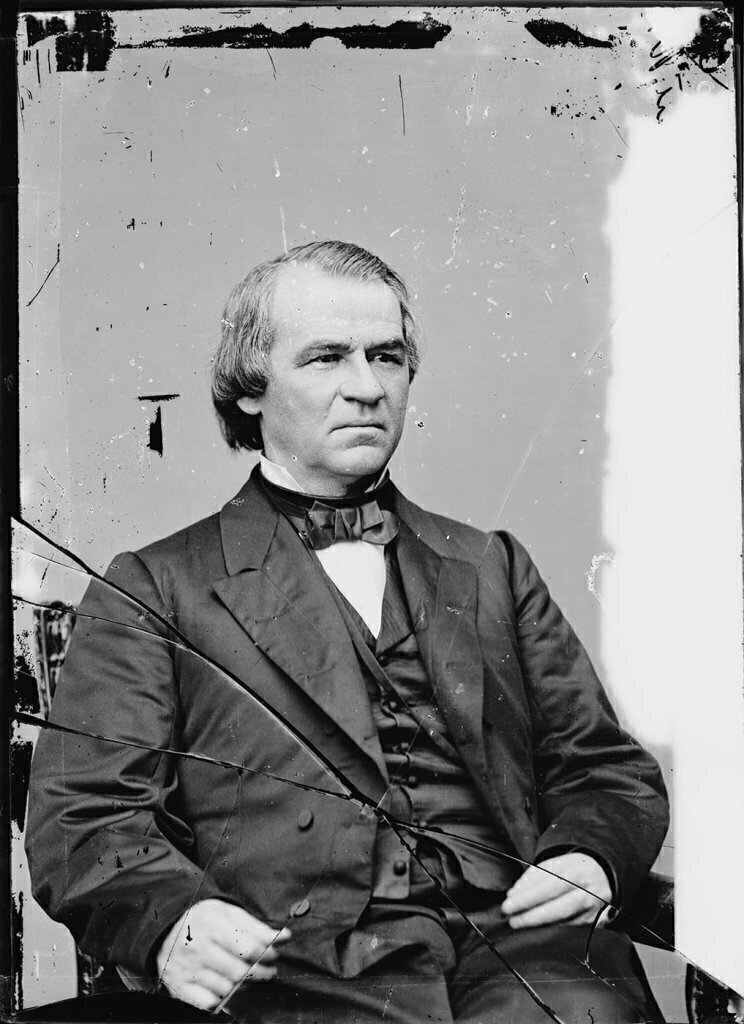

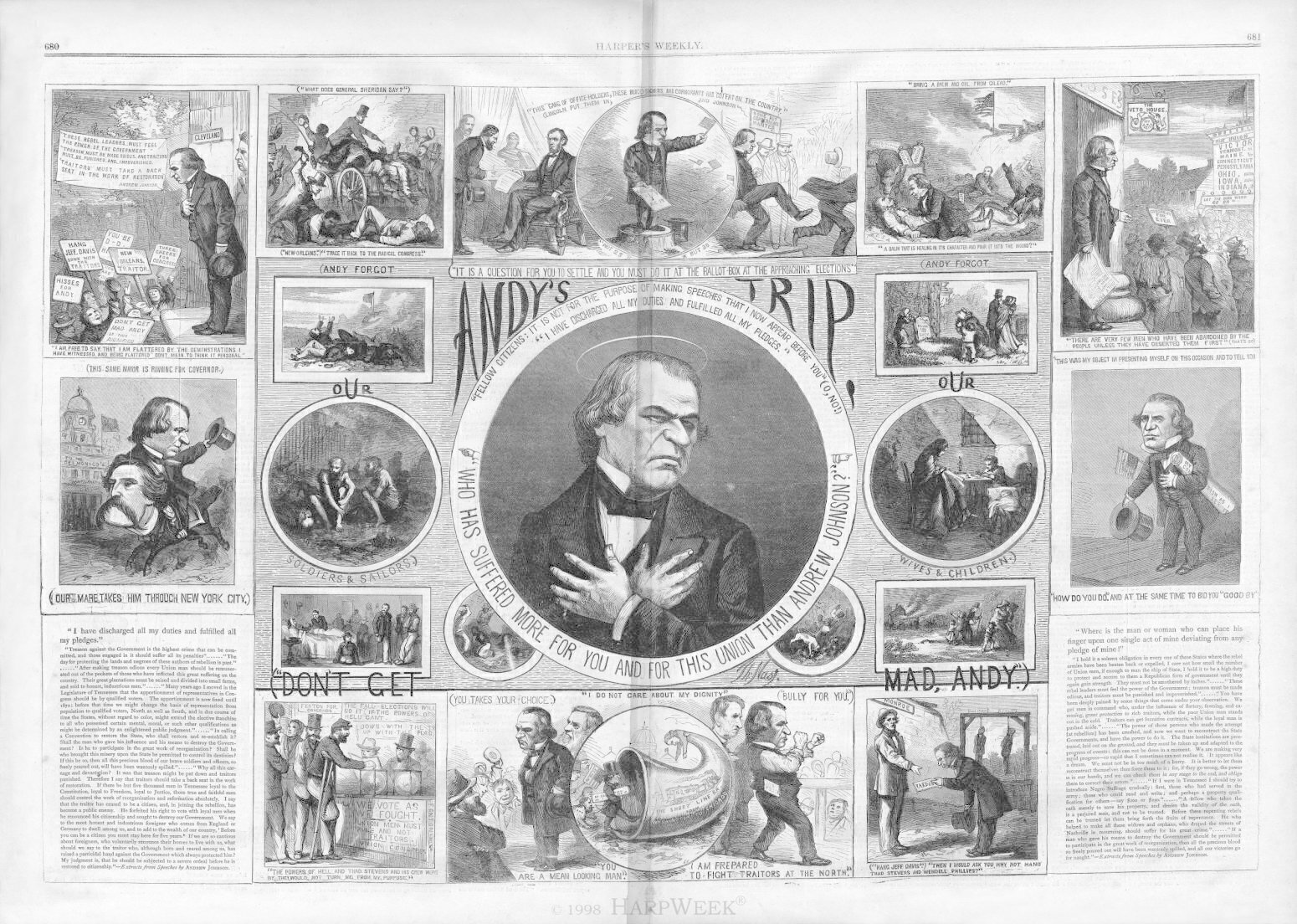

After Abraham Lincoln's assassination, Vice President Andrew Johnson became president. While Lincoln had always shown a mix of flexibility and prudence about abolition and African-American rights, Johnson was hostile towards black people. His conciliatory attitude towards the former Confederate states—and acceptance of white supremacy—led to clashes with Congressional Republicans.

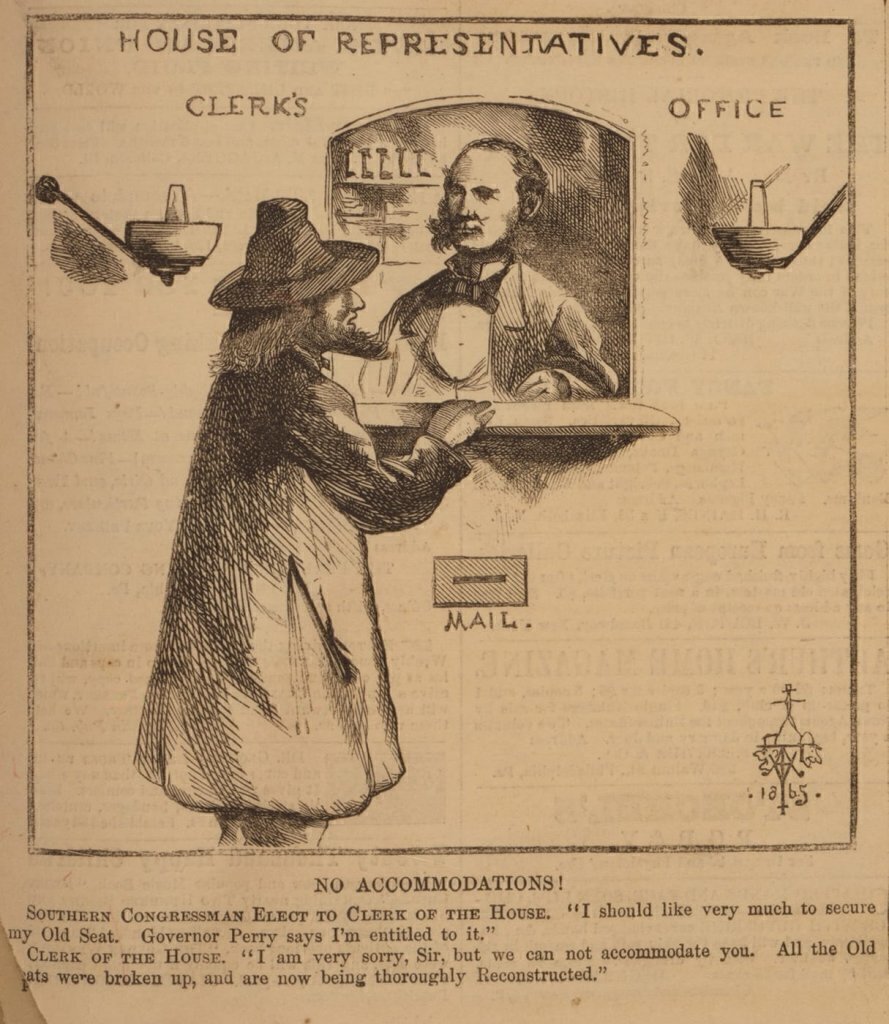

December 4, 1865

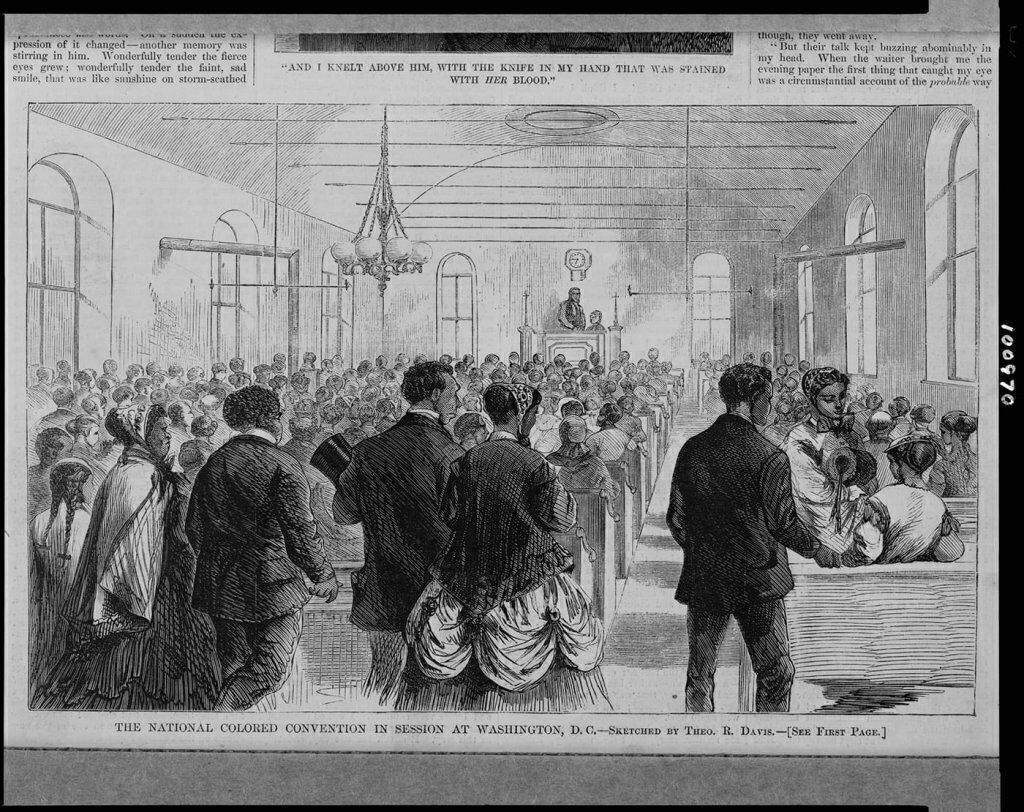

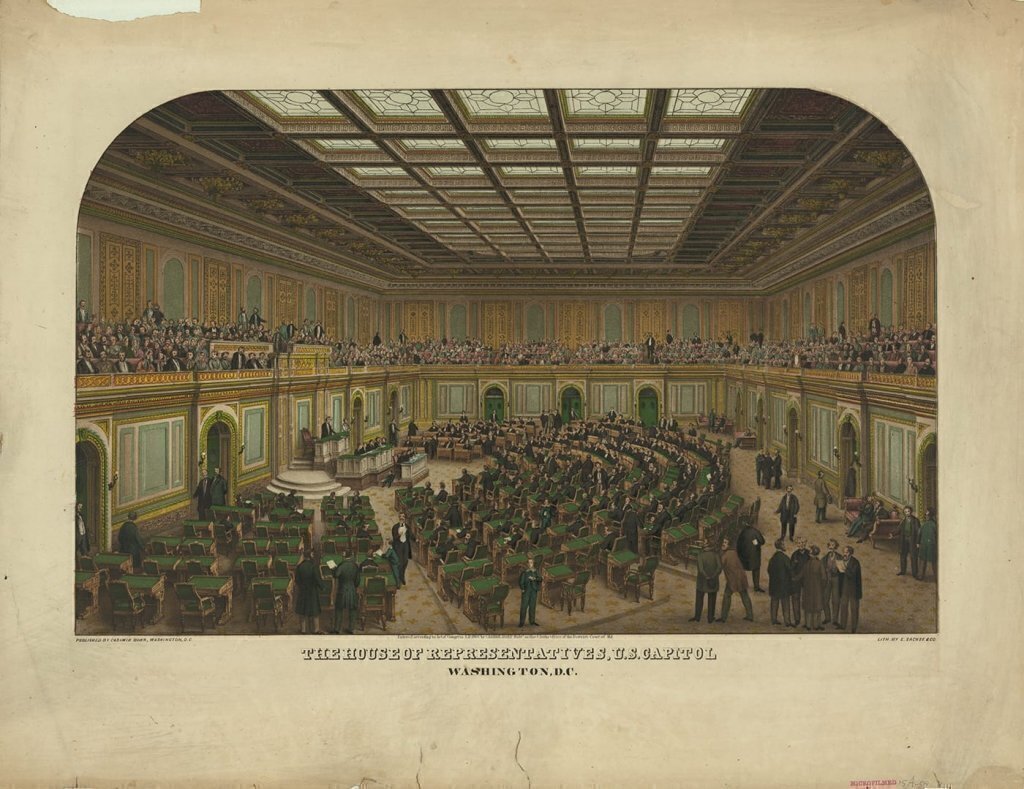

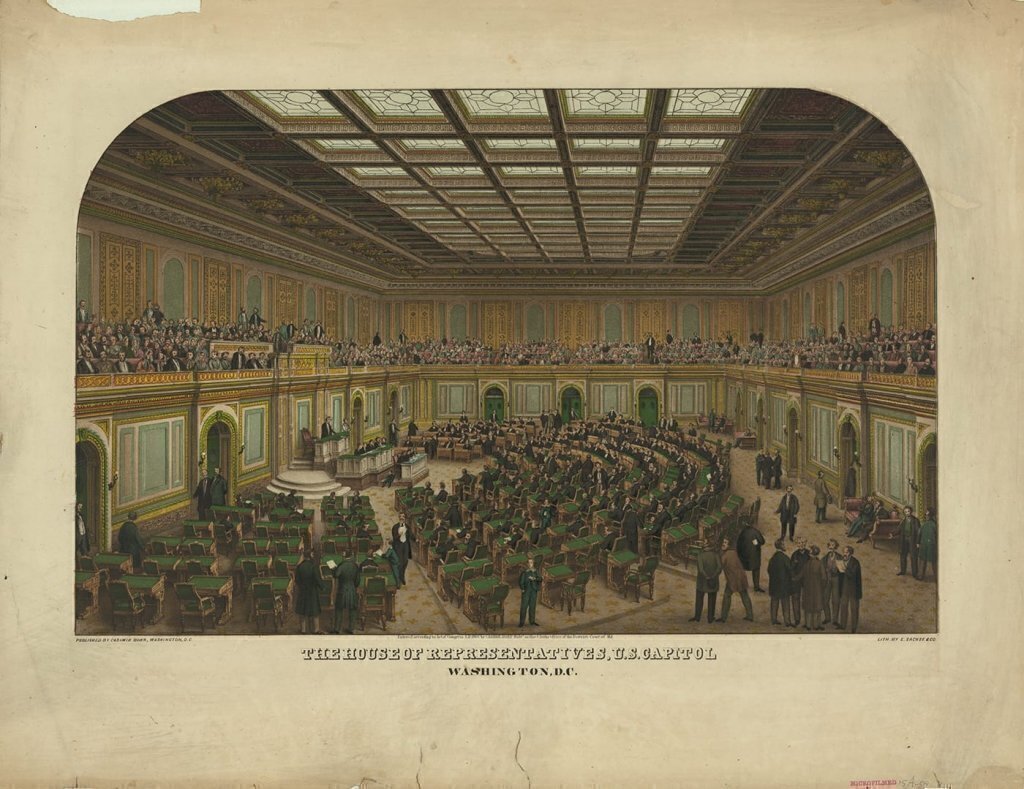

Members of Congress gathered in Washington, D.C., to take their seats for the beginning of a new session. If the Republicans hoped to take control of Reconstruction, they needed to act quickly.

December 6, 1865

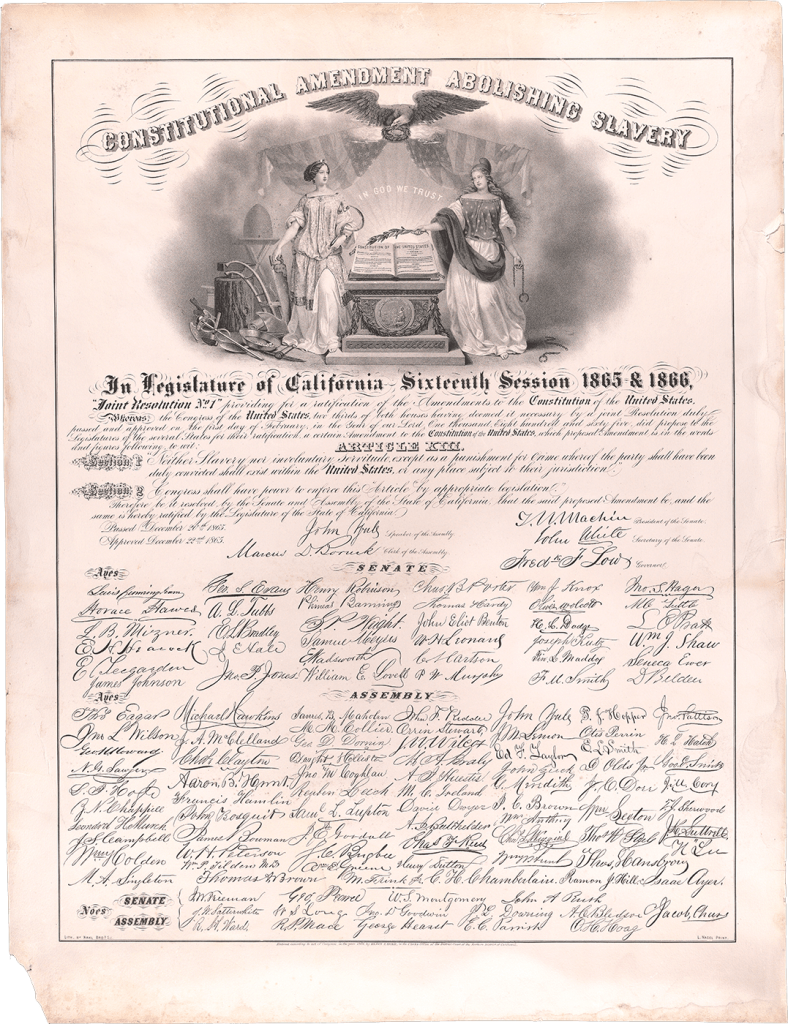

The 13th Amendment ended slavery everywhere in the United States. However, it did not address many other key issues facing post-Civil War America, including the meaning of freedom, equality, and citizenship now that slavery was abolished.

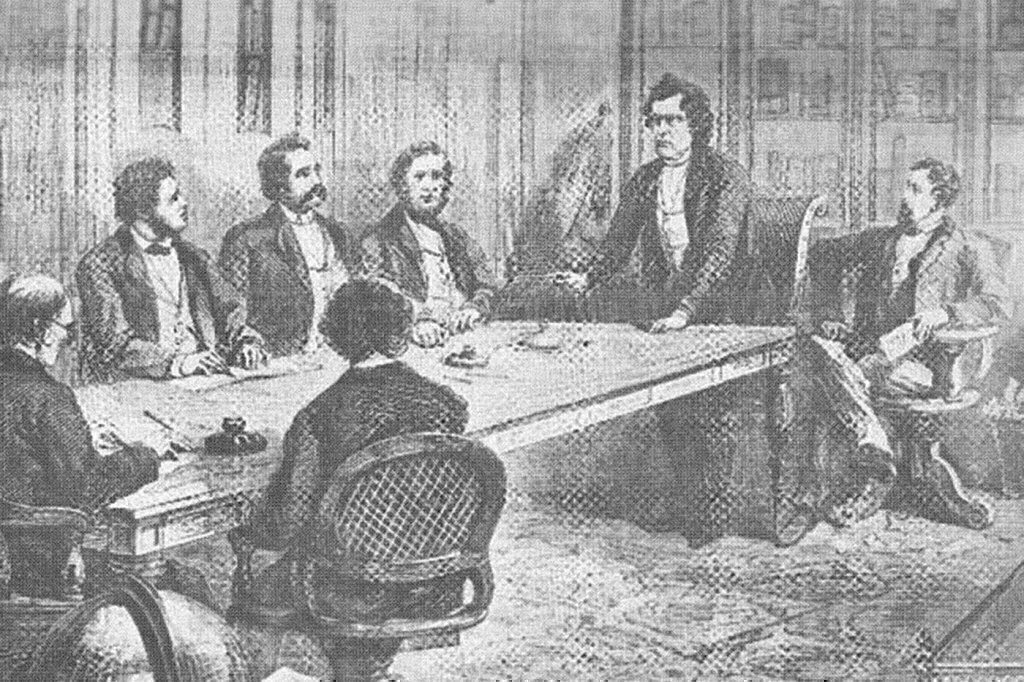

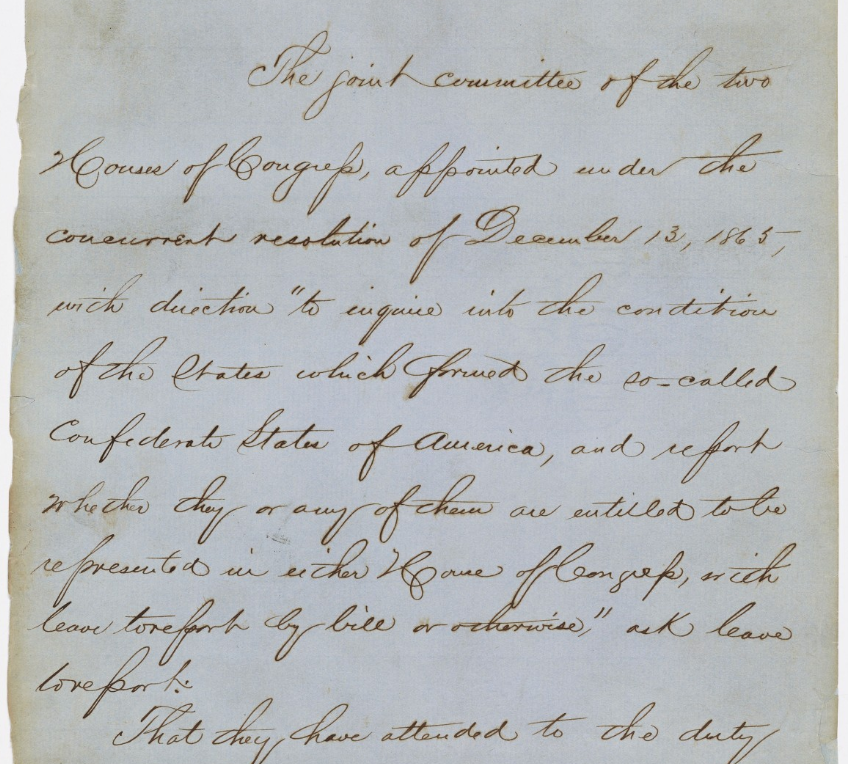

December 13, 1865

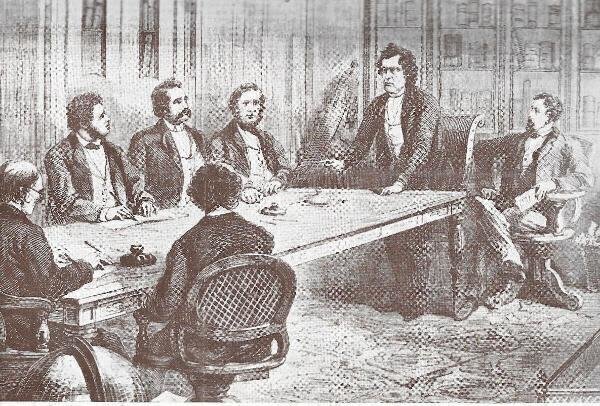

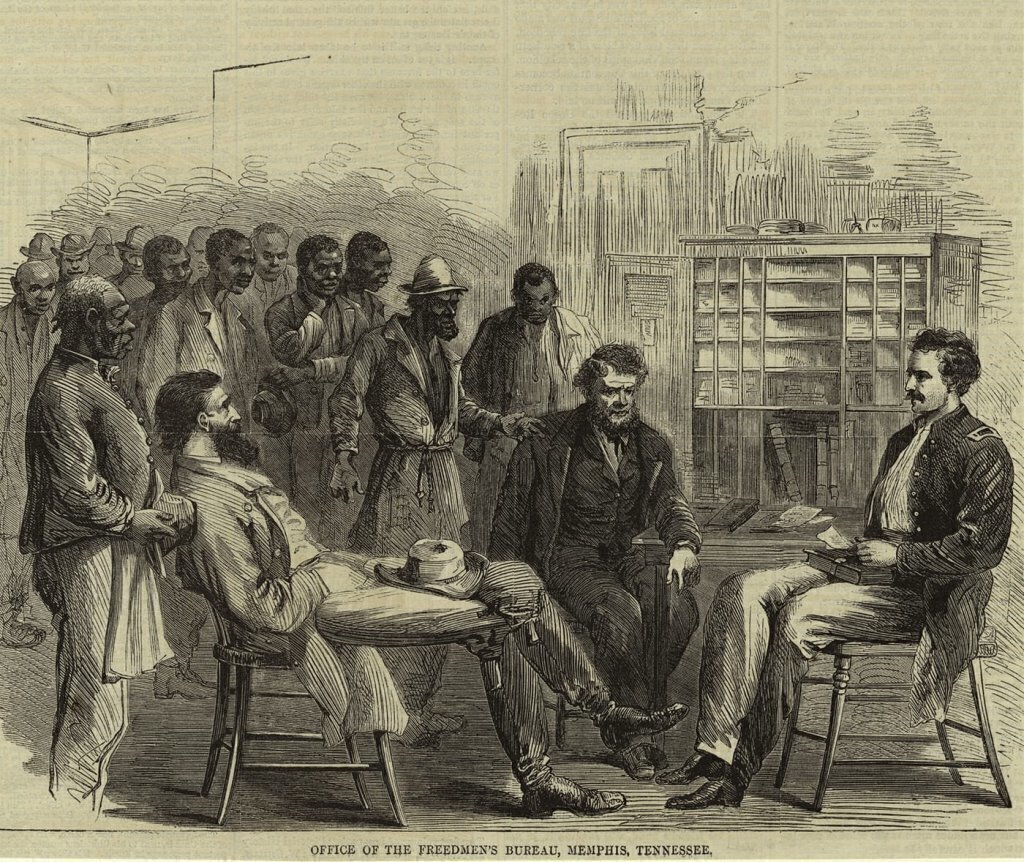

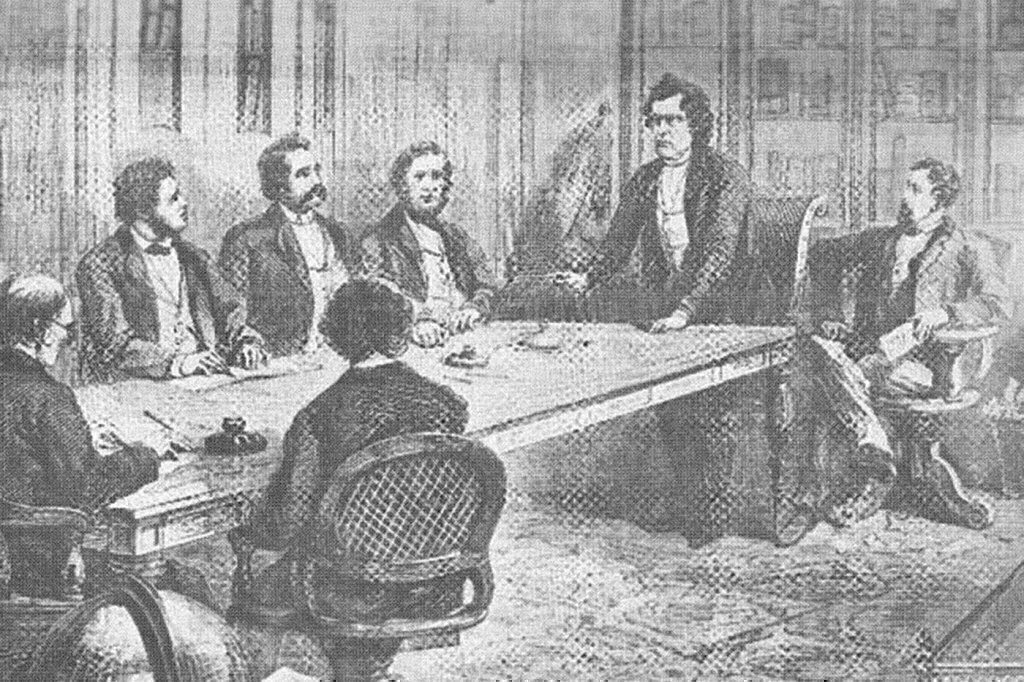

Congress formed a 15-member committee to investigate the post-war South and consider what legislation might be necessary to reunite the nation. The committee focused on several issues: Southern white abuses of African Americans; the possible expansion of Southern white political power in Congress; the Confederacy's war debt; and the political status of ex-Confederates.

January 12, 1866

This draft focused on ending racial discrimination. It was considered by the Joint Committee. Moved to sub-committee of the Joint Committee.

January 12, 1866

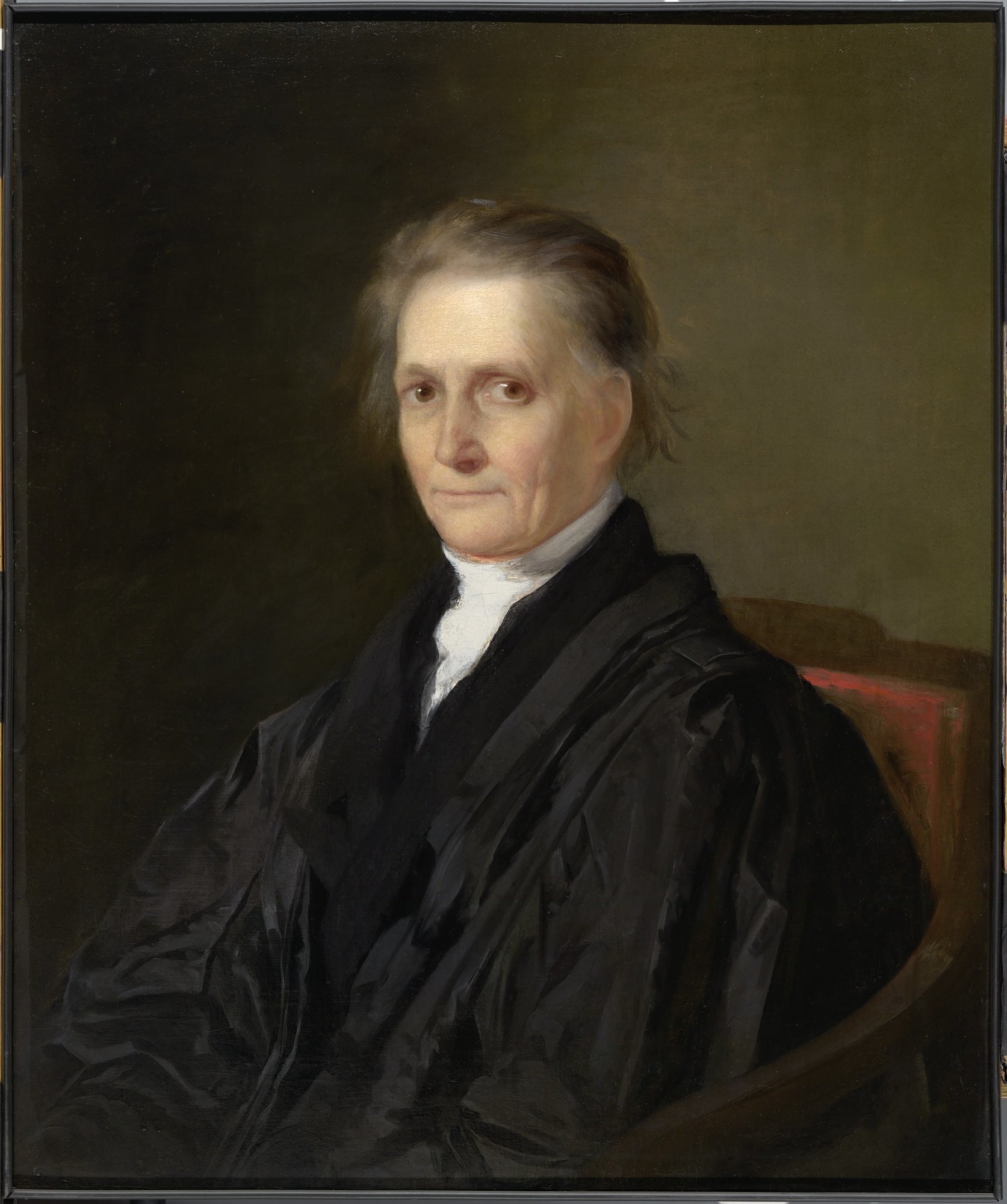

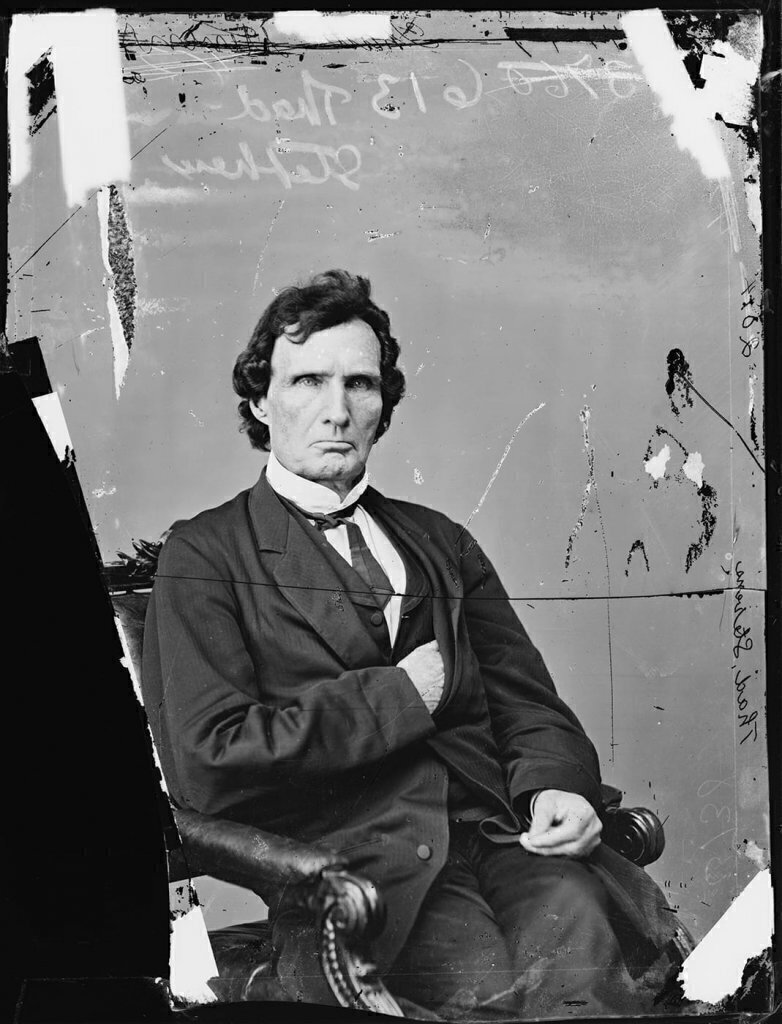

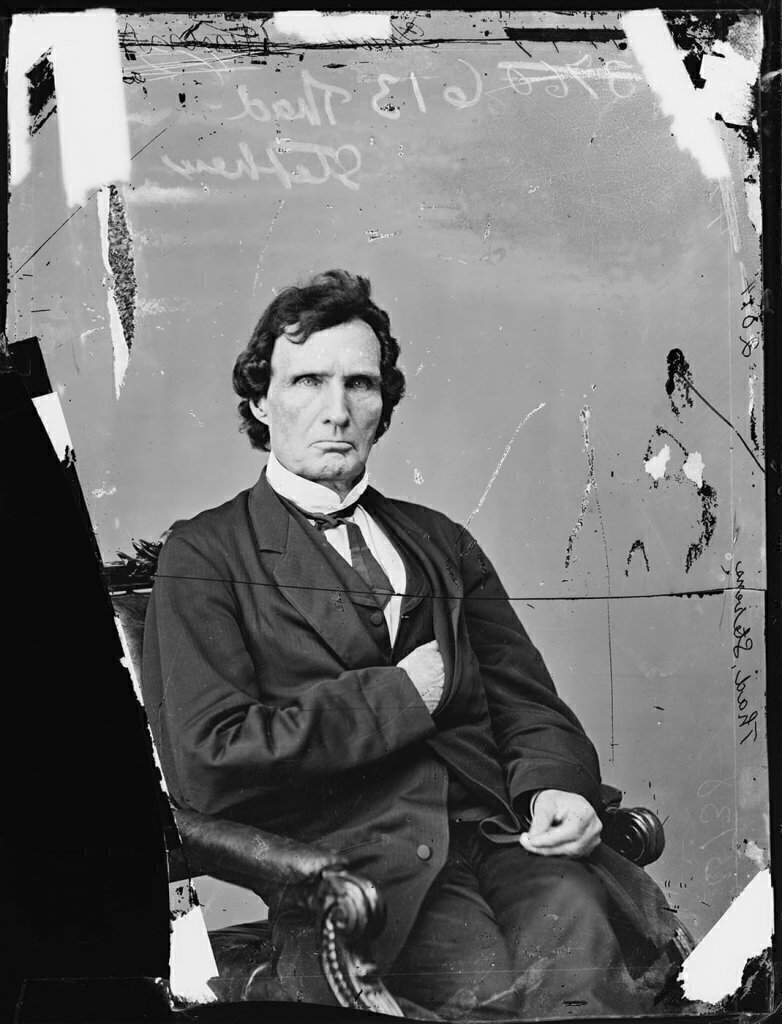

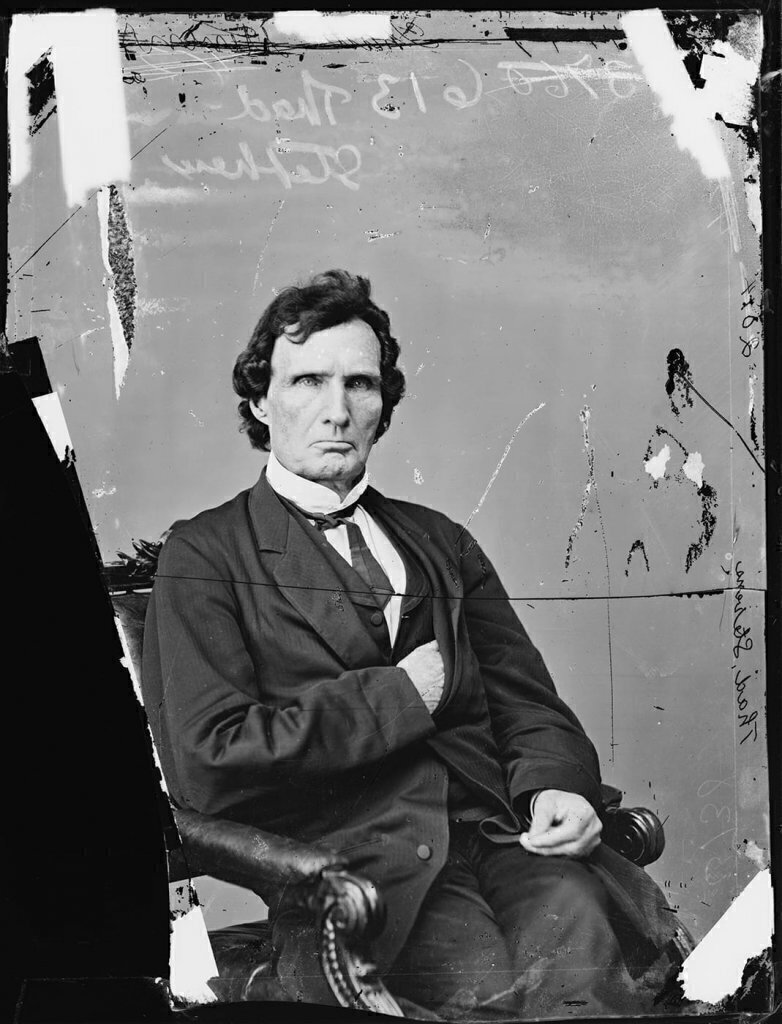

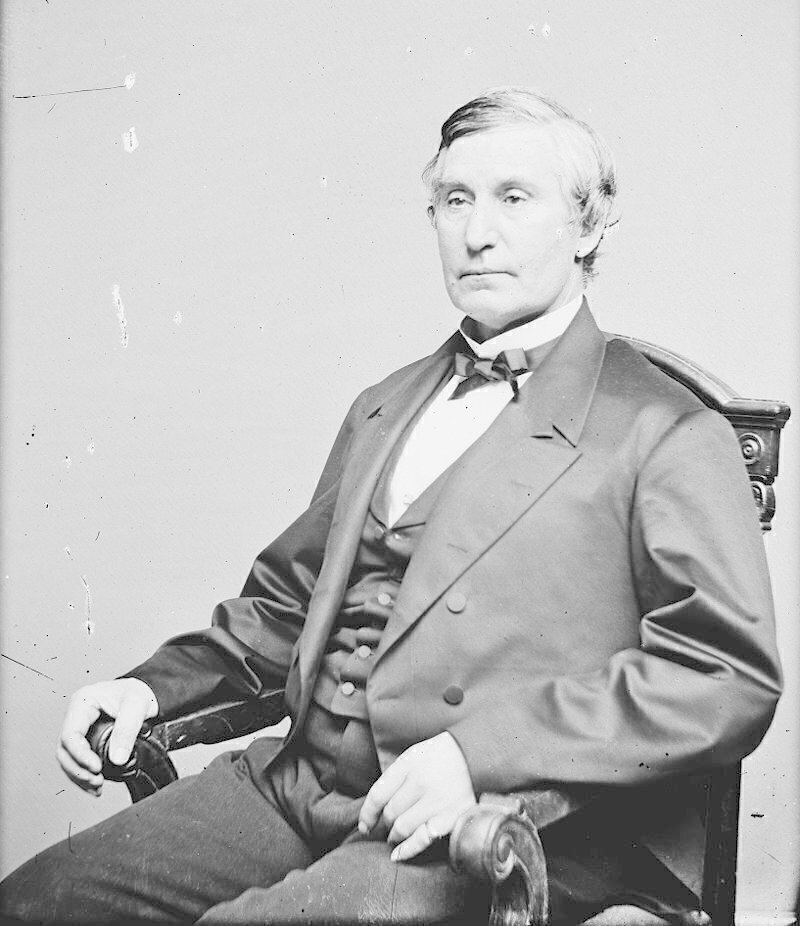

Thaddeus Stevens

U.S. Representative, Republican, Pennsylvania

All laws, state or national, shall operate impartially and equally on all persons This provision covered “all persons” and promoted equality. It also explicitly protected against both state and national abuses. without regard to race or color. This proposal focused squarely on racial discrimination, while the final text of the amendment applied more broadly.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 12, 1866

Thaddeus Stevens

U.S. Representative, Republican, Pennsylvania

All laws, state or national, shall operate impartially and equally on all persons This provision covered “all persons” and promoted equality. It also explicitly protected against both state and national abuses. without regard to race or color. This proposal focused squarely on racial discrimination, while the final text of the amendment applied more broadly.

Select a Document

January 12, 1866

This draft gave Congress the power to enforce equal protection for the rights of life, liberty, and property. It was considered by the Joint Committee.

January 12, 1866

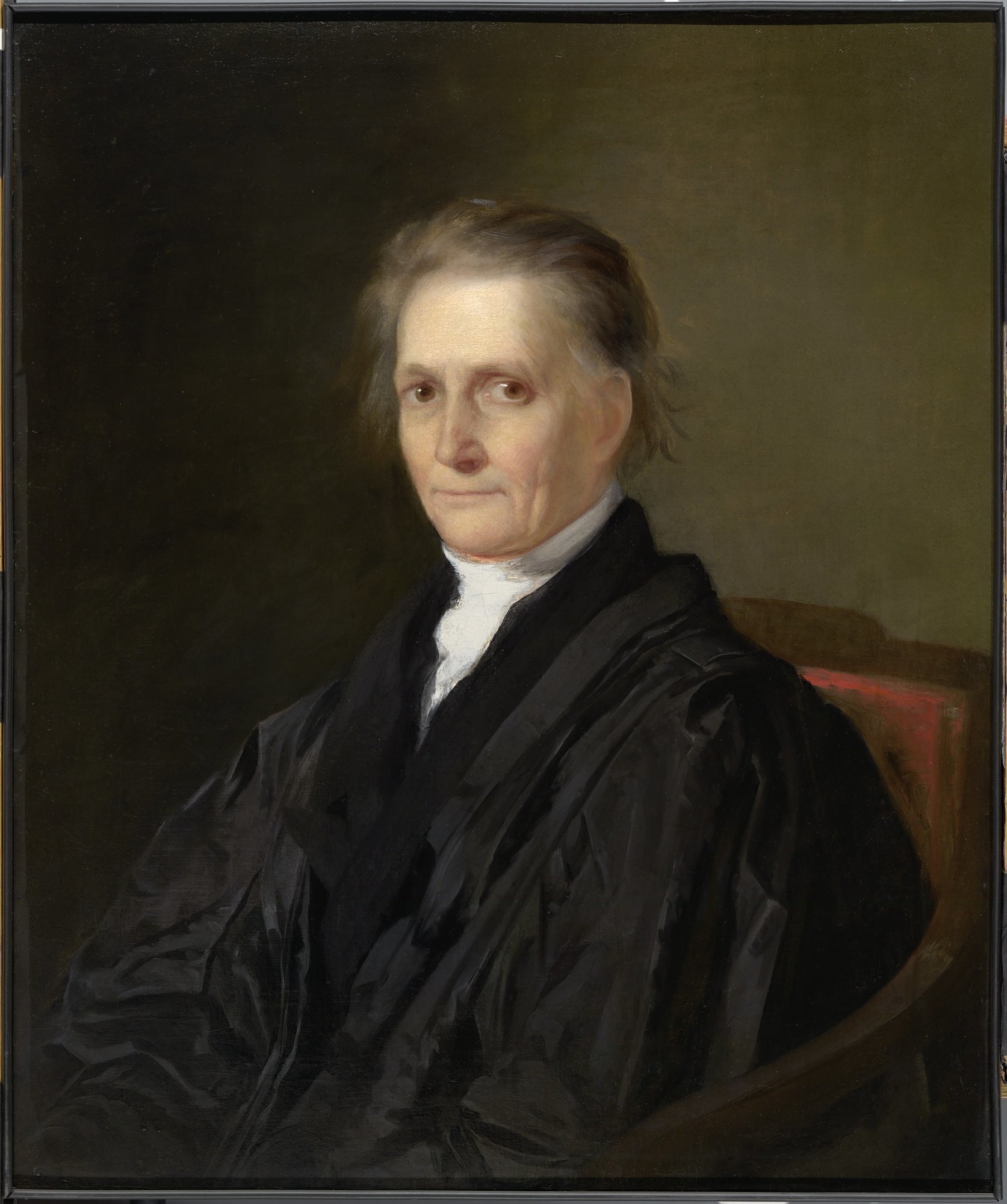

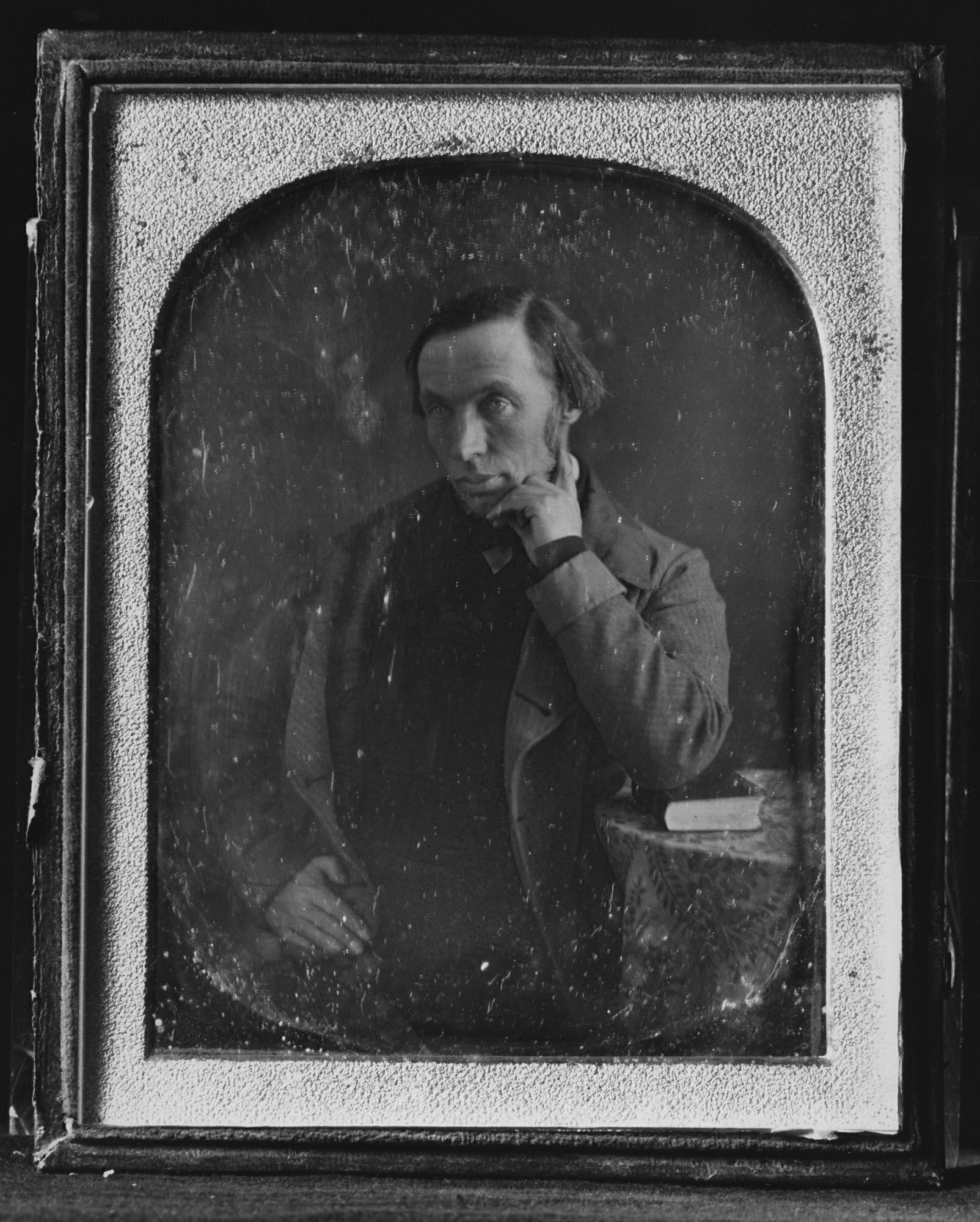

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper Drawing on Article I's Necessary and Proper Clause, this text empowered Congress to protect civil rights. Bingham wanted to ensure the Constitution granted Congress this authority, since Republicans did not trust the courts after Dred Scott. to secure to all persons in every state within this Union equal protection in their rights of life, liberty and property. While the Constitution was originally silent on the Declaration's promise of equality, Bingham's proposal sought to write it into the Constitution. The language “life, liberty and property” also parallels the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 12, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper Drawing on Article I's Necessary and Proper Clause, this text empowered Congress to protect civil rights. Bingham wanted to ensure the Constitution granted Congress this authority, since Republicans did not trust the courts after Dred Scott. to secure to all persons in every state within this Union equal protection in their rights of life, liberty and property. While the Constitution was originally silent on the Declaration's promise of equality, Bingham's proposal sought to write it into the Constitution. The language “life, liberty and property” also parallels the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Select a Document

January 22, 1866

This Joint Committee draft addressed congressional representation and sought to reduce representation for jurisdictions that allowed racial discrimination in voting. Stevens introduced it in the House on January 22, 1866. House debated, decided to remove “direct taxes,” and then adopted (120-46). Senate passed (25-22), but did not reach the two-thirds threshold.

January 22, 1866

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

39th Congress

Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed: Provided, That whenever the elective franchise shall be denied or abridged in any State on account of race or color, all persons of such race or color shall be excluded from the basis of representation. With slavery abolished, representation in Congress and direct taxes would now be determined based on “the whole number of persons,” including African Americans. Republicans feared that this would empower the white South in future Congresses. Since the Constitution left the issue of voting to the states, Reconstruction Republicans feared the disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South. They looked to promote (but not force) black voting and to limit white Southern power.While not forcing Southern states to grant voting rights to African Americans, this language would punish states that disenfranchised African Americans by lowering their representation in Congress.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 22, 1866

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

39th Congress

Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed: Provided, That whenever the elective franchise shall be denied or abridged in any State on account of race or color, all persons of such race or color shall be excluded from the basis of representation. With slavery abolished, representation in Congress and direct taxes would now be determined based on “the whole number of persons,” including African Americans. Republicans feared that this would empower the white South in future Congresses. Since the Constitution left the issue of voting to the states, Reconstruction Republicans feared the disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South. They looked to promote (but not force) black voting and to limit white Southern power.While not forcing Southern states to grant voting rights to African Americans, this language would punish states that disenfranchised African Americans by lowering their representation in Congress.

Select a Document

January 27, 1866

This draft granted Congress the power to protect rights and promote equality. It was considered by the Joint Committee. The Joint Committee vote failed. The Committee revised the language on February 3.

January 27, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper Drawing on Article I's Necessary and Proper Clause, this text empowered Congress to protect civil rights. Bingham wanted to ensure the Constitution granted Congress this authority, since Republicans did not trust the courts after Dred Scott. to secure to all persons in every state within this Union equal protection in their rights of life, liberty and property. While the Constitution was originally silent on the Declaration's promise of equality, Bingham's proposal sought to write it into the Constitution. The language “life, liberty and property” also parallels the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 27, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper Drawing on Article I's Necessary and Proper Clause, this text empowered Congress to protect civil rights. Bingham wanted to ensure the Constitution granted Congress this authority, since Republicans did not trust the courts after Dred Scott. to secure to all persons in every state within this Union equal protection in their rights of life, liberty and property. While the Constitution was originally silent on the Declaration's promise of equality, Bingham's proposal sought to write it into the Constitution. The language “life, liberty and property” also parallels the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Select a Document

February 3, 1866

This draft added “privileges and immunities” language that mirrored Article IV. In the final text, Bingham would abandon Article IV's language and instead protect the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Joint Committee passed this revised text (9-4) and sent to both houses of Congress.

February 3, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The Congress shall have the power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper Drawing on Article I's Necessary and Proper Clause, this text empowered Congress to protect civil rights. Bingham wanted to ensure the Constitution granted Congress this authority, since Republicans did not trust the courts after Dred Scott. to secure to the citizens of each State all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States; Republicans debated this text, with some turning to Corfield v. Coryell, a court decision defining it as covering a set of fundamental rights. Bingham later revised it, protecting the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” and to all persons in the several States equal protection in the rights of life, liberty, and property. Covering “all persons,” this text shifted from “full” protection back to “equal” protection. It also again incorporated "life, liberty, and property,” paralleling the Fifth Amendment.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.February 3, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The Congress shall have the power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper Drawing on Article I's Necessary and Proper Clause, this text empowered Congress to protect civil rights. Bingham wanted to ensure the Constitution granted Congress this authority, since Republicans did not trust the courts after Dred Scott. to secure to the citizens of each State all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States; Republicans debated this text, with some turning to Corfield v. Coryell, a court decision defining it as covering a set of fundamental rights. Bingham later revised it, protecting the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” and to all persons in the several States equal protection in the rights of life, liberty, and property. Covering “all persons,” this text shifted from “full” protection back to “equal” protection. It also again incorporated "life, liberty, and property,” paralleling the Fifth Amendment.

Select a Document

February 28, 1866

The Joint Committee sent John Bingham's proposed amendment to Congress on February 10, 1866. This proposal borrowed language from the Constitution's Privileges and Immunities Clause and empowered Congress to protect civil rights. After debate, Congress decided to postpone consideration until April.

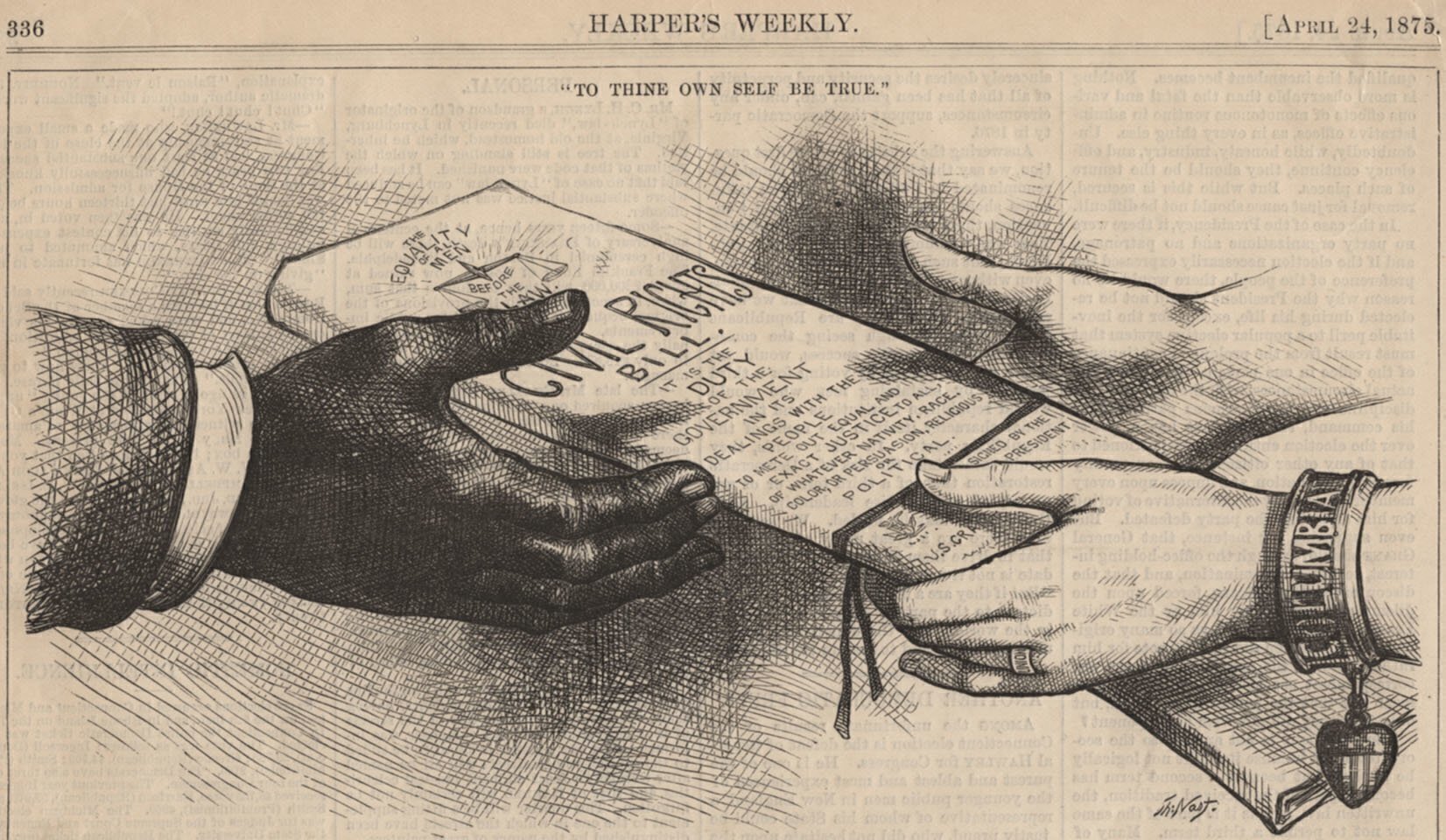

With the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Republicans sought to attack the South's discriminatory “black codes” and protect civil rights. President Johnson vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode his veto. After months of rising tensions, Johnson's veto signaled a decisive break with Congressional Republicans over Reconstruction policy.

This expansive draft provided protections for civil rights and voting, while tackling other issues like the Confederate war debt. It also gave Congress the power to enforce its measures. Bingham wanted to add a section that provided equal protection and protected property rights, but he failed. The Joint Committee made a few other changes, and then adopted each section.

April 21, 1866

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

39th Congress

No discrimination shall be made by any state, nor by the United States, as to the civil rights of persons because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. This language explicitly covered discrimination by both the national and state governments. While the final text covered “all persons,” this language focused squarely on racial discrimination. From and after the fourth day of July, in the year one thousand eight hundred seventy-six, no discrimination shall be made by any state, nor by the United States, as to the enjoyment by classes of persons of the right of suffrage, because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Until the fourth day of July, one thousand eight hundred and seventy-six, no class of persons, as to the right of any of whom to suffrage discrimination shall be made by any state, because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, shall be included in the basis of representation. This language ended racial discrimination in voting, an issue that still divided Republicans. To ease the transition, the text delayed implementation until July 4, 1876. The committee would remove this clause—leaving the issue to the 15th Amendment. This text also addressed Republican fears that the white South would count African Americans for purposes of congressional representation, but deny them the vote. It contained a sunset provision, after which racial discrimination in voting would end. Debts incurred in aid of insurrection or of war against the Union, and claims of compensation for loss of involuntary service or labor, shall not be paid by any State nor by the United States. Republicans feared the United States would be forced to pay Confederate war debt or compensation for emancipation once white Southerners regained power in Congress. This provision would prevent that. Congress shall have power to enforce by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. Congress shall have power to enforce by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.April 21, 1866

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

39th Congress

No discrimination shall be made by any state, nor by the United States, as to the civil rights of persons because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. This language explicitly covered discrimination by both the national and state governments. While the final text covered “all persons,” this language focused squarely on racial discrimination. From and after the fourth day of July, in the year one thousand eight hundred seventy-six, no discrimination shall be made by any state, nor by the United States, as to the enjoyment by classes of persons of the right of suffrage, because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Until the fourth day of July, one thousand eight hundred and seventy-six, no class of persons, as to the right of any of whom to suffrage discrimination shall be made by any state, because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, shall be included in the basis of representation. This language ended racial discrimination in voting, an issue that still divided Republicans. To ease the transition, the text delayed implementation until July 4, 1876. The committee would remove this clause—leaving the issue to the 15th Amendment. This text also addressed Republican fears that the white South would count African Americans for purposes of congressional representation, but deny them the vote. It contained a sunset provision, after which racial discrimination in voting would end. Debts incurred in aid of insurrection or of war against the Union, and claims of compensation for loss of involuntary service or labor, shall not be paid by any State nor by the United States. Republicans feared the United States would be forced to pay Confederate war debt or compensation for emancipation once white Southerners regained power in Congress. This provision would prevent that. Congress shall have power to enforce by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. Congress shall have power to enforce by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Select a Document

In late April, the Joint Committee hammered out the draft that eventually became the 14th Amendment. The committee decided to combine several different issues into a single, bundled amendment. Each house of Congress debated and revised that proposal, then approved it and sent it to the states for ratification.

This draft included protection for due process, the privileges or immunities of U.S. citizenship, and equal protection. It is very similar to the final text, but without a citizenship clause. Joint Committee passed (10-3) and sent to both houses of Congress.

April 28, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; Before this, the Bill of Rights only protected against abuses by the national government. States could abuse rights like free speech and religious liberty. This text protected those “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens against state abuses. nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law, Matching language in the 5th Amendment, this clause protected “any person” from denial of their “life, liberty or property” without the government providing some sort of fair procedure first. nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. This provision wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise of equality into the Constitution. It ensured “equal protection” for “any person”—going beyond racial discrimination.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.April 28, 1866

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; Before this, the Bill of Rights only protected against abuses by the national government. States could abuse rights like free speech and religious liberty. This text protected those “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens against state abuses. nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law, Matching language in the 5th Amendment, this clause protected “any person” from denial of their “life, liberty or property” without the government providing some sort of fair procedure first. nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. This provision wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise of equality into the Constitution. It ensured “equal protection” for “any person”—going beyond racial discrimination.

Select a Document

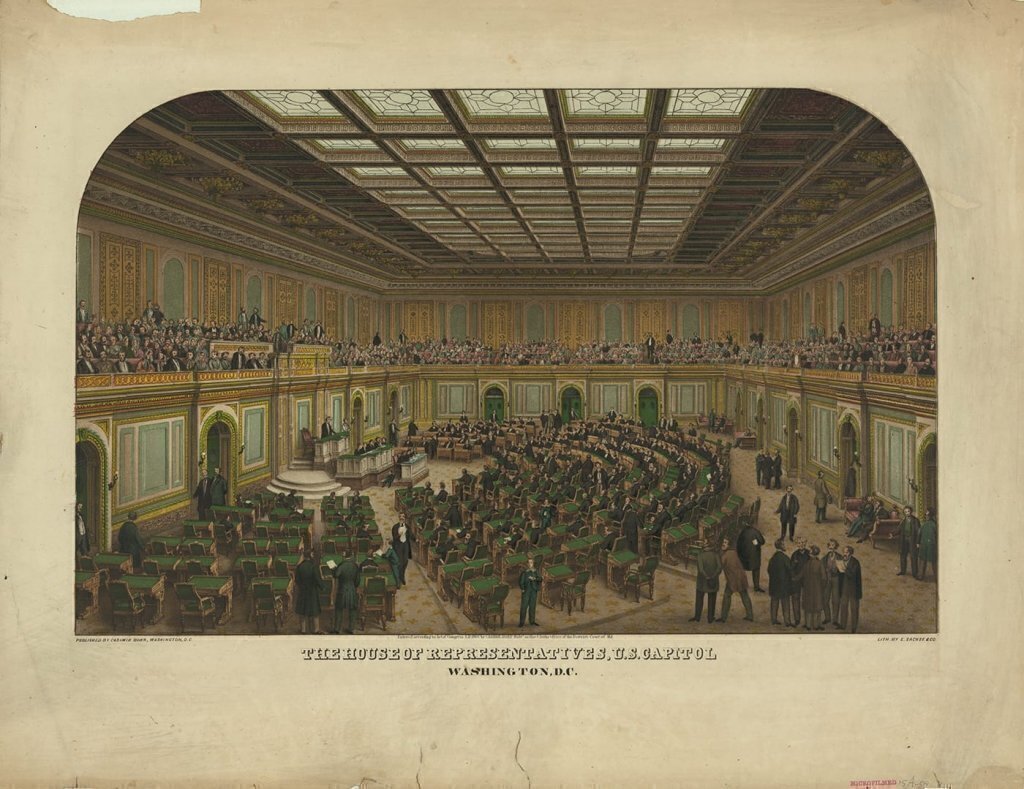

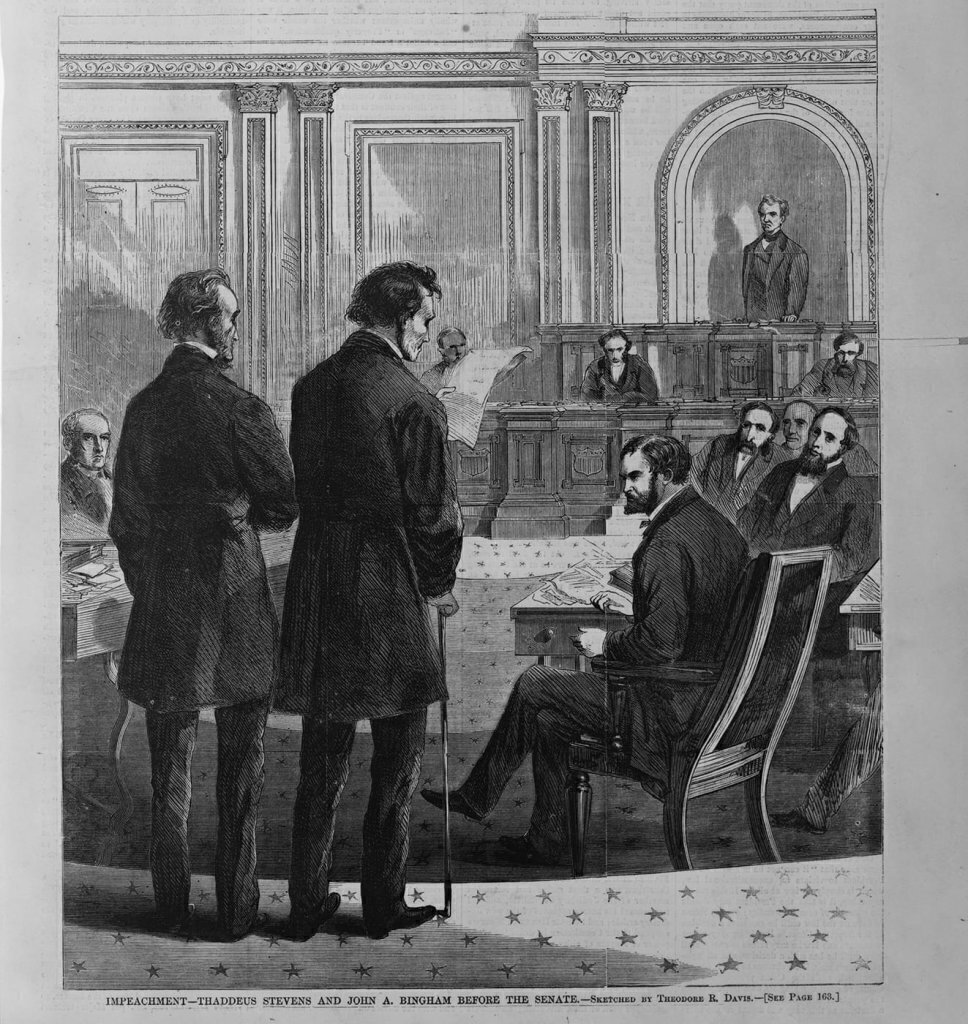

Thaddeus Stevens introduced the proposed 14th Amendment in the House. Members debated the proposal on the House floor, but its language survived without major revisions.

.jpg)

The House passed the proposed amendment on May 10, 1866.

This draft was similar to the final amendment text, but did not include a citizenship clause. During its debates, Congress would also revise the provisions addressing war debt and the political status of ex-Confederates. House passed (128-37) and sent to the Senate. The Senate would add the Citizenship Clause, replace Section Three, and consider alterations to Section Four.

May 10, 1866

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

39th Congress

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; Before this, the Bill of Rights only protected against abuses by the national government. States could abuse rights like free speech and religious liberty. This text protected those “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens against state abuses. nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; This language ensured fair procedures before anyone was denied “life, liberty, or property.” nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. This provision wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise of equality into the Constitution. It ensured “equal protection” for “any person”—going beyond racial discrimination. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But whenever in any State the elective franchise shall be denied to any portion of its male citizens not less than twenty-one years of age, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion or other crime, the basis of representation in such State shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens not less than twenty-one years of age. This compromise measure penalized Southern states for disenfranchising African Americans. However, it also used the word “male”—an explicit gender-based restriction that infuriated many women's rights activists. Until the 4th day of July, in the year 1870, all persons who voluntarily adhered to the late insurrection, giving it aid and comfort, shall be excluded from the right to vote for Representatives in Congress and for electors for the President and Vice President of the United States. Republicans feared ex-Confederate political power. This language denied many former rebels of the right to vote for president and Congress until July 4, 1870. Neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation already incurred, or which may hereafter be incurred, in aid of insurrection or of war against the United States, or any claim for compensation for loss of involuntary service or labor. Republicans feared being forced to pay the Confederate war debt or compensation for emancipation once white Southerners regained power in Congress. This provision prevented that. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. This language ensured that Congress would have enforcement powers, paralleling language used in the 13th Amendment. Some Republicans feared that Congress did not have the power to pass civil rights legislation under the existing Constitution.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.May 10, 1866

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

39th Congress

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; Before this, the Bill of Rights only protected against abuses by the national government. States could abuse rights like free speech and religious liberty. This text protected those “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens against state abuses. nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; This language ensured fair procedures before anyone was denied “life, liberty, or property.” nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. This provision wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise of equality into the Constitution. It ensured “equal protection” for “any person”—going beyond racial discrimination. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But whenever in any State the elective franchise shall be denied to any portion of its male citizens not less than twenty-one years of age, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion or other crime, the basis of representation in such State shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens not less than twenty-one years of age. This compromise measure penalized Southern states for disenfranchising African Americans. However, it also used the word “male”—an explicit gender-based restriction that infuriated many women's rights activists. Until the 4th day of July, in the year 1870, all persons who voluntarily adhered to the late insurrection, giving it aid and comfort, shall be excluded from the right to vote for Representatives in Congress and for electors for the President and Vice President of the United States. Republicans feared ex-Confederate political power. This language denied many former rebels of the right to vote for president and Congress until July 4, 1870. Neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation already incurred, or which may hereafter be incurred, in aid of insurrection or of war against the United States, or any claim for compensation for loss of involuntary service or labor. Republicans feared being forced to pay the Confederate war debt or compensation for emancipation once white Southerners regained power in Congress. This provision prevented that. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. This language ensured that Congress would have enforcement powers, paralleling language used in the 13th Amendment. Some Republicans feared that Congress did not have the power to pass civil rights legislation under the existing Constitution.

Select a Document

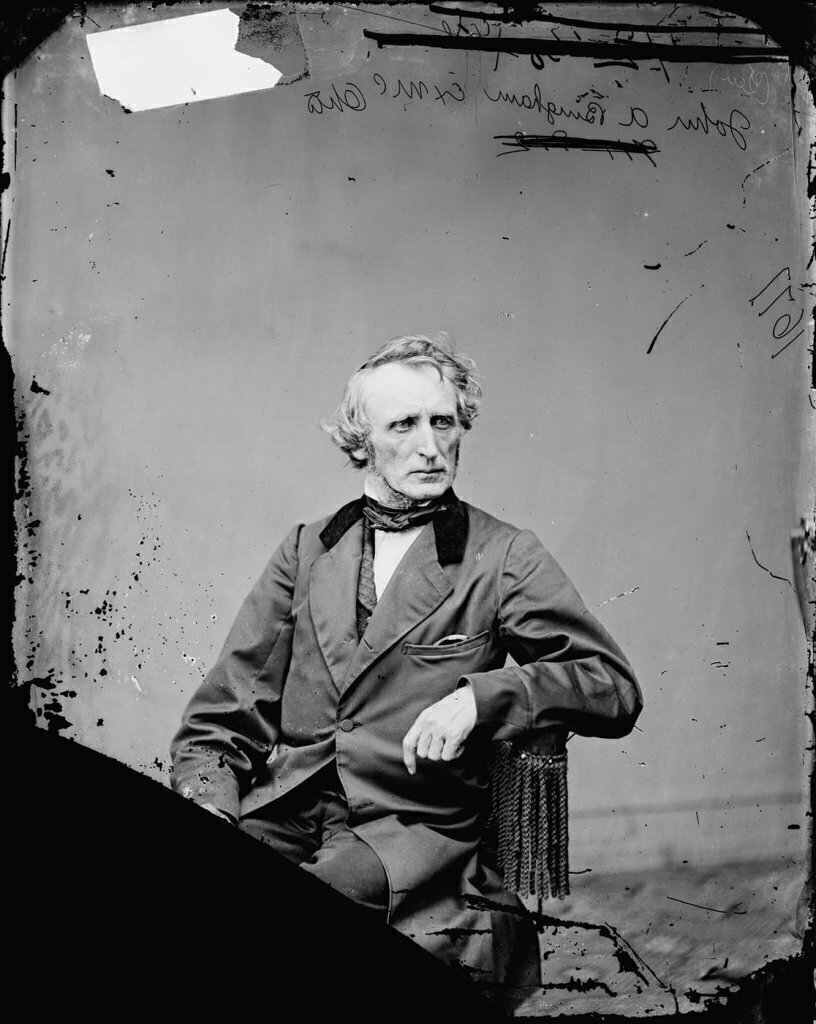

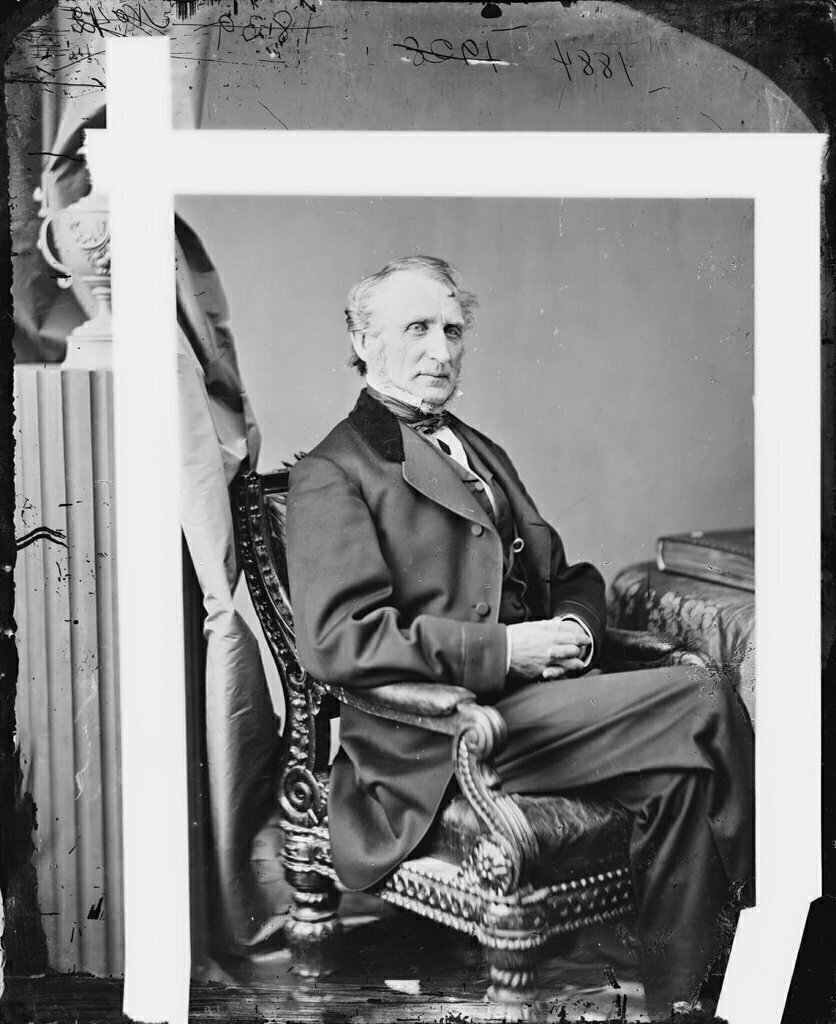

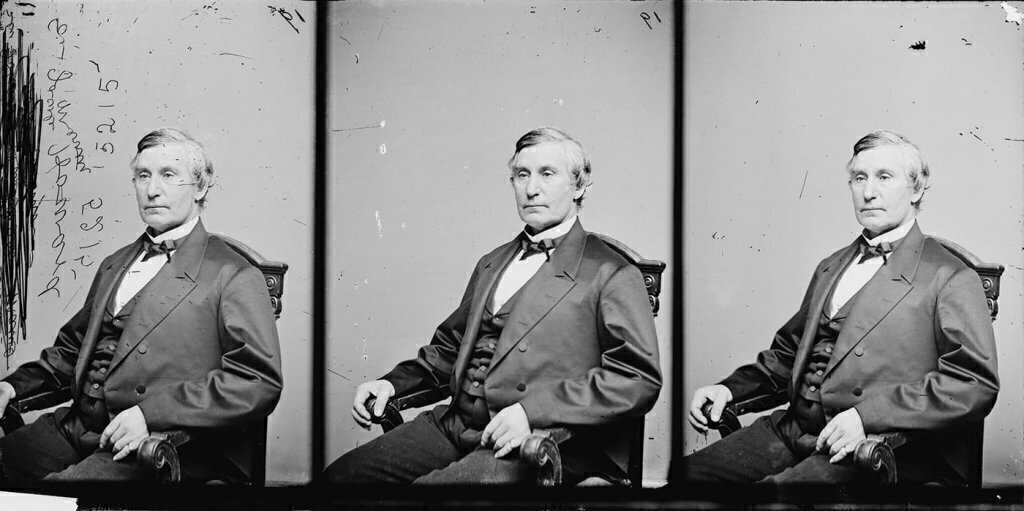

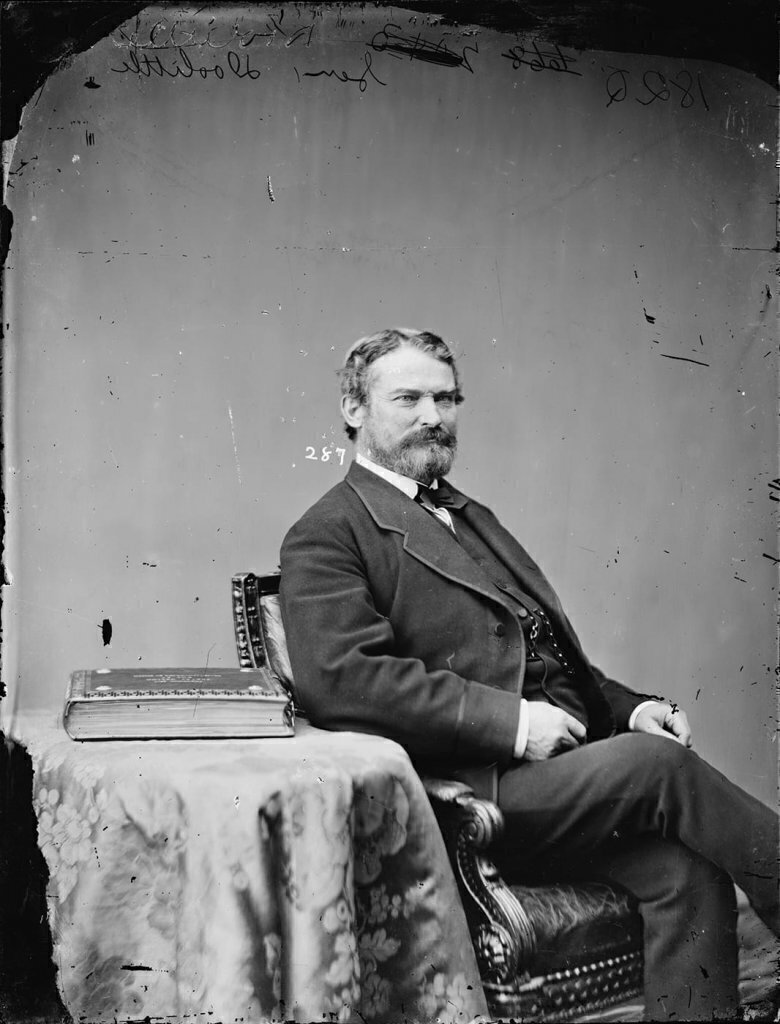

Senator Jacob Howard introduced the proposed 14th Amendment in the Senate. In the debates that followed, the Senate made some significant revisions.

This new language included the Citizenship Clause, which was added by the Senate. The Senate also proposed new text regarding former rebels holding office and revised language about war debt. Senate passed revised amendment with citizenship clause (33-11) and sent to the House.

May 29, 1866

Jacob Howard

U.S. Senator, Republican, Michigan

All persons born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the States wherein they reside. Republicans added this clause near the end of the debates. It guaranteed that everyone born on American soil became a U.S. citizen, explicitly overturning Dred Scott. This settled the issue of African-American citizenship. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or an elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State Legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof; but Congress may, by a vote of two thirds of each House, remove such disability. Republicans feared a return to power for ex-Confederate leaders. This provision ended office-holding for high-ranking ex-Confederates, reserving to Congress the power to lift these disabilities with a two-thirds vote in each House. The obligations of the United States incurred in suppressing insurrection, or in defense of the Union or for payment of bounties or pensions incident thereto, shall remain inviolate. This provision protected the nation's debt obligations. Republicans feared that white Southerners might deny these obligations—which included pensions for Union soldiers and their widows—once they returned to power. This protected those payments.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.May 29, 1866

Jacob Howard

U.S. Senator, Republican, Michigan

All persons born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the States wherein they reside. Republicans added this clause near the end of the debates. It guaranteed that everyone born on American soil became a U.S. citizen, explicitly overturning Dred Scott. This settled the issue of African-American citizenship. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or an elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State Legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof; but Congress may, by a vote of two thirds of each House, remove such disability. Republicans feared a return to power for ex-Confederate leaders. This provision ended office-holding for high-ranking ex-Confederates, reserving to Congress the power to lift these disabilities with a two-thirds vote in each House. The obligations of the United States incurred in suppressing insurrection, or in defense of the Union or for payment of bounties or pensions incident thereto, shall remain inviolate. This provision protected the nation's debt obligations. Republicans feared that white Southerners might deny these obligations—which included pensions for Union soldiers and their widows—once they returned to power. This protected those payments.

Select a Document

The Joint Committee issued its report on conditions in the post-Civil War South, and the Senate passed a revised version of the proposed amendment. The debate over the amendment turned back to the House, which now needed to approve the Senate's version.

The House accepted the Senate's revisions and passed the proposed amendment. It was then sent to the states for ratification.

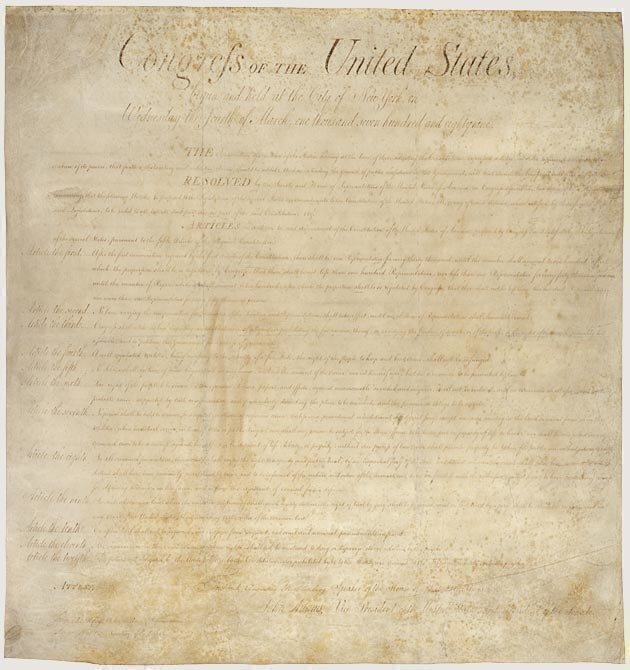

The 14th Amendment set new constitutional baselines for post-Civil War America—granting additional powers to Congress and providing protections for citizenship, rights, and equality. This is the final version of the text, as last amended by the Senate. In 1866, after the Senate passed the amendment (33-11), the House passed it (120-32). It was then sent to the states for ratification and was officially adopted in 1868.

June 13, 1866

39th Congress

Final Amendment

Section One

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. This text, known as the Citizenship Clause, declared that everyone born on American soil is a citizen of the United States. The provision overturned Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) and ended a decades-long debate about whether free black people were American citizens. Finally, natural-born African Americans could lay claim to the promise of equal citizenship. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; This clause demanded that states respect the “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens. Originally, the Bill of Rights bound only the national government, not the states. Therefore, states could violate key protections like free speech and religious liberty. Many Southern states did—for example, by banning abolitionist speech in the lead-up to the Civil War. nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; This clause banned states from denying any person due process of law. Without national guarantees in place, Reconstruction Republicans worried that African Americans might not be permitted to enjoy even basic rights. This provision ensured that all people would receive fair treatment from state authorities before any loss of life, liberty, or property. nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

While seeking safeguards for those formerly enslaved, this part of the amendment reached more broadly, promising “equal protection of the laws” for “any person” in the United States. The original document was silent on the issue of equality, but with this amendment, Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise into the Constitution. Section Two

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section Two concerns representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. The original Constitution counted three-fifths of the enslaved population for congressional representation. With the end of slavery, “the whole number of persons” in the ex-Confederate states, including African Americans, would be counted. Reconstruction Republicans feared that this would empower the white South in future Congresses. Section Two addressed this concern by reducing representation in the House for any state that denied black men the right to vote. Section Three

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section Three ended office-holding rights for high-ranking ex-Confederates. It also granted Congress the power to lift these restrictions. Since Republicans feared a return to power for ex-Confederate leaders, Congress had debated a range of issues, such as which former rebels to punish and how broadly any punishment should sweep. The final text had a narrow scope. Section Four

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section Four served two purposes. First, it protected the national debt from attempts by future Democratic Congresses to reject paying it. Second, it prohibited the United States from paying any of the debt incurred by the Confederacy—including claims made over the loss of emancipated slaves. Section Five

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. Paralleling language in the 13th Amendment, Section Five granted Congress new power to enforce its protections and pass civil rights legislation. Skeptical of the Supreme Court after the Dred Scott decision (1857), Reconstruction Republicans wanted to grant Congress these powers to protect the civil rights of all Americans, particularly African Americans in the South.

June 13, 1866

39th Congress

Final Amendment

Section One

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. This text, known as the Citizenship Clause, declared that everyone born on American soil is a citizen of the United States. The provision overturned Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) and ended a decades-long debate about whether free black people were American citizens. Finally, natural-born African Americans could lay claim to the promise of equal citizenship. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; This clause demanded that states respect the “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens. Originally, the Bill of Rights bound only the national government, not the states. Therefore, states could violate key protections like free speech and religious liberty. Many Southern states did—for example, by banning abolitionist speech in the lead-up to the Civil War. nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; This clause banned states from denying any person due process of law. Without national guarantees in place, Reconstruction Republicans worried that African Americans might not be permitted to enjoy even basic rights. This provision ensured that all people would receive fair treatment from state authorities before any loss of life, liberty, or property. nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

While seeking safeguards for those formerly enslaved, this part of the amendment reached more broadly, promising “equal protection of the laws” for “any person” in the United States. The original document was silent on the issue of equality, but with this amendment, Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise into the Constitution. Section Two

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section Two concerns representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. The original Constitution counted three-fifths of the enslaved population for congressional representation. With the end of slavery, “the whole number of persons” in the ex-Confederate states, including African Americans, would be counted. Reconstruction Republicans feared that this would empower the white South in future Congresses. Section Two addressed this concern by reducing representation in the House for any state that denied black men the right to vote. Section Three

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section Three ended office-holding rights for high-ranking ex-Confederates. It also granted Congress the power to lift these restrictions. Since Republicans feared a return to power for ex-Confederate leaders, Congress had debated a range of issues, such as which former rebels to punish and how broadly any punishment should sweep. The final text had a narrow scope. Section Four

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section Four served two purposes. First, it protected the national debt from attempts by future Democratic Congresses to reject paying it. Second, it prohibited the United States from paying any of the debt incurred by the Confederacy—including claims made over the loss of emancipated slaves. Section Five

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. Paralleling language in the 13th Amendment, Section Five granted Congress new power to enforce its protections and pass civil rights legislation. Skeptical of the Supreme Court after the Dred Scott decision (1857), Reconstruction Republicans wanted to grant Congress these powers to protect the civil rights of all Americans, particularly African Americans in the South.